There is no doubt that current societal standards for female beauty inordinately emphasize the desirability of thinness–and thinness at a level that is impossible for most women to achieve by healthy means. In their pervasiveness, the mass media are powerful conveyors of this sociocultural ideal. – Marika Tiggemann

The tension between the modern public and the topic of diet remains an ongoing issue that segues into many related topics such as the obesity epidemic and the rise of terminal illnesses in the current generations. In the quote above,1 Tiggemann succinctly captures the current state of things in modern American society, touching upon the sub-issues of the targeting of women, health concerns over dieting, media representation of this phenomenon, and the prevalent consciousness of body image.Though these issues are pressing and seem large at first glance, it is possible to break it down and analyze its origins by merely flipping it on its head. As media coverage is instantaneous and always relevant to contemporary issues, viewing them through the lens of the media can reveal the prominence of an issue to the audience of the time. Therefore, it is possible to explore how the word “diet” even became a verb, evolving from its innocent beginnings as a noun meaning simply “the food and drink regularly eaten or drunk by a person or group”2 to an eventual alternate meaning which is “to limit the food and/or drink that you have, especially in order to lose weight.”3 For the purpose of this essay, I am focusing on each edition of mainstream magazines The New Yorker, Ebony, and Life in the period from the 1940s to the 1980s to study the trends and patterns in the media, including advertisements, articles, and diction, more specifically the use of words such as “diet” and “health.” By looking in detail at these magazines, I will explore how the word “diet” changed in meaning for women, what that entails in terms of female’s concern over nutrition, and answer the pressing question of how we got here.

One of the most notable features of this cultural phenomenon is how it has left its mark on American lexicon by coining a new definition for the word “diet,” as previously mentioned. Though the slight change may seem insignificant, the connotation of the word – thanks to the new definition – marks a paradigm shift in the public’s view on nutrition and its relevance to self. In 1942, increased public awareness on the relationship between food and health is fueled by broader scientific research of nutrition. For example, a Life Magazine article advertising Kellogg’s Whole Grain Cereal, promotes the cereal by emphasizing the “nutritive value” that the product contains and how it is highly beneficial for the digestive system and health (Fig. 1).4 The implementation of specialized terms like “Thiamin (Vitamin B), Niacin and Iron” in the article demonstrates a scientific understanding of the food components. As scientific research readily advances in the 1940s, more articles are published but this time not promoting a product, but a healthier diet or, as referred to in the title of one of the articles, a “good diet”(Fig. 2).5 This article in 1943 offers specific amounts (in milligrams) of Vitamin C, A, D and other nutrients that are needed to “keep your body healthy,”6 along with a picture of a sample diet plan consisting mostly of whole foods like carrots, potatoes, and apples. Specific foods such as milk are now pronounced “the perfect food,” solely based on its nutritive components fitting the requirements for a “good diet” (Fig. 3).7 The three articles during this period are similar in that the word “diet” is referred to as an intake of food that is good for your health and body. However, the implication of the word doesn’t stay consistent as time progresses.

To observe if there was any pattern that came along with the inconsistency in the meaning of “diet,” I recorded the number of articles and advertisements concerning nutrition and calculated the frequency of their primary focus per decade (Fig. 4).8 Health, diet, calories, fat and nutrition appeared to be the most prominent topics discussed in the magazines. The observations from articles discussed above were in accordance with my findings, which demonstrated that the highest cultural mindshare percentage (almost fifty) in the 1940s was in fact, health. Nutrition-related articles were fairly saturated, up until the 1950s where its mindshare became taken up by calorie and fat-related publications. An article in 1954 on the nutritional benefits of using lemon as seasoning perfectly demonstrates this trend (Fig. 5).9 Although the primary focus in the article is still “health,” the term “low-calorie” is being introduced into the rhetoric of nutrition. Even more interestingly, the coverage on diet stayed fairly consistent throughout the decades with around thirty percent mindshare. Yet, the term’s meaning was being noticeably re-constructed in the 1950s to fit a new definition of diet that is more commonly used in the modern day: to lose weight and to limit calories.

Once the meaning of the word diet changes, the market also changes in a fundamental way. We can see this by looking closely at a “Tasti Diet” advertisement from 1954 (Fig. 6).10 The advertisement invokes a new use of the term diet, as phrased by its title, saying a doctor puts his patient, Tillie Lewis, “on a diet” and further promotes the product by emphasizing its “low-calorie” content and ability to “control” or “reduce weight.” The product is seemingly proud of its wide variety of “36 kinds of food” which includes peaches in syrup and chocolate fudge. However, as “tasty” as this diet might actually be, its main selling point is the limited calories that it provides. Therefore, this case is one of the examples to elaborate on the increased percentage of articles in the 1950s concerning “weight” and “calories.”11

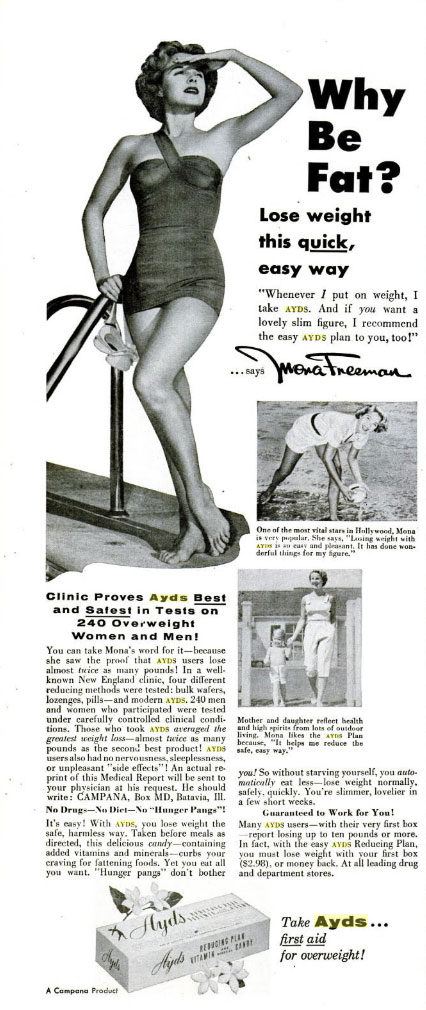

Both the “Tasti Diet” brand’s name and marketing strategy hint at the old definition of diet being reinvented into this newer, more dominant definition. As the new definition is being exposed to the general public and incorporated through articles and advertisements, the market continues to introduce products that accord with this new trend of limiting calories and losing weight. As noticed in the case of the “Tasti Diet,” the new products are not necessarily healthy and just aim to help the consumer lose weight. A diet candy called “Ayds,” introduced by the Life Magazine in 1952 becomes one of the more popular new products that especially concentrates on calories and weight (Fig. 7).12 The advertisement promotes this diet candy through an interview with a female celebrity, Hedy Lamarr, who consumes the product, along with a trademark phrase “Slim the Way the Stars Slim.” The effects of this diet candy are described as absolutely magical: lose fat without dieting, feel healthier and control over-eating. It is no wonder that with such claims the product rapidly gained popularity and more coverage in further years. From 1955 to 1958, the caramel was frequently promoted as a solution to being “overweight”(Fig. 8)13 and the growing demand was evident through the overwhelming amount of articles where women shared their weight-loss stories using this product (Fig. 9).14 At that point in time, the definition of diet has fully evolved from healthy food consumption to depriving yourself and miraculously losing weight by eating this commercially-produced candy.

If compared to the previously mentioned articles in the 1940s, where everyone was told to eat whole foods and vegetables to keep the body healthy, it seems unbelievable that only after 10 years, eating magic candy to shed pounds and look “star-like” is the trend. One explanation to this drastic shift is that there was simply not enough knowledge on nutrition and health in the 1940s to produce complex supplements like the “Ayds” candy. During that period, extensive research was conducted on nutrition, as evidenced by the use of nutritional jargon in the articles.15 16 In the 1950s, with an advanced scientific understanding of healthy whole foods, people became able to produce unhealthy processed foods, which contained all the needed nutrients for a “good diet” in low-calorie supplements. This is certainly quite ironic since prior to research, the articles actually showed a greater understanding of what a healthy diet should incorporate in comparison to when research had progressed.

As if weight-controlling candy wasn’t bad enough, in the 1970s the market becomes saturated with diet pills that help limit food consumption altogether. The conversation isn’t even about whether to consume whole or processed foods, but taking medication to not consume anything and eliminate calories. The following is illustrated through the high saturation of advertisements on diet pills in Ebony Magazine in 1978. One of the examples is an advertisement that sells an “anti-calorie capsule program,” which claims to help “create a calorie-deficit” and “shrink your body’s fat cells” (Fig. 10).17 The explanation mentions how medical science has proven that your body can “melt away inches like never before,” confirming how scientific research has in fact led to the creation of these disastrous products. In 30 years, people become most literally “anti-calorie,”18 to the extent that they developed medication to become a fat-burning machine.

The marketing strategies applied in the discussed articles and advertisements are meant to perfectly target the fears and demands of the popular culture in America. Frederick Zimmerman discusses this relationship that exists between the market and the public, to justify an increased food consumption in the modern day.19 He uses several studies to explain how one of the marketing and advertising strategies works on the consumer’s “unconscious mechanism,” to increase awareness or generate inclinations towards certain products, in order to increase consumption of those brands.

During the period from the 1950s to 1970s, the food industry is filled with big food processors that apply the same marketing strategy that Zimmerman analyzes to effectively advertise their products. One market niche turns out to be women, whose fear of increasing body size could be exploited in a way to brand more processed foods as special solutions to the problem of dieting. The previously mentioned “Tasti Diet” advertisement demonstrates how processed food and the term “diet” was becoming gender-specific (Fig. 6).20 Besides every image in the publication depicting women, the brand’s label is even designed so that a woman’s head separates the words “Tasti” and “Diet”. Everything seems to suggest that the woman’s head is Tillie Lewis’, for whom the advertisement also provides a descriptive narrative. This is also a marketing strategy to establish ethos with the audience, by presenting Tillie Lewis as both a prime customer and the company’s logo. In this way, the article is insinuating Tillie Lewis’s direct relationship with food consumption and implicitly targeting women in diet practices. The advertisement also promotes their “peaches in syrup” not as any other old peaches, but new and tasty “diet” peaches. In this way, the addition of apparent value to food processing with a label “diet,” grows to develop into a niche market that insidiously targets women.

From a different perspective, rather than the market pushing towards a new gender-specific definition of “diet,” women are the ones driving this diet industry. While it is true that, especially during the 1960s, there are several articles that begin to anchor “desirable body weight” standards to women (Fig. 11),21 there hasn’t been a large number of studies to show how these advertisements actually affected women’s views about their expectations and themselves. In addition, even by profusely advertising candy and pills to pressure women into becoming slim,22 they were not guaranteed to take it seriously or personally. A psychological study conducted in 2011 questioned whether individuals truly get affected by body-depreciating or diet-encouraging advertisement.23 The experiment recorded data from two groups of people (male and female), one being exposed to self-deflating advertisements while the other one was not, with the aim to find out whether “exposure to ideal body imagery characters affect body satisfaction.” The data results surprisingly showed that self-deflating advertisements had no negative impact on the experimental group. The study explains that when faced with a self-deprecating advertisement which presented an unachievable body ideal, the individuals simply ignored it. While it’s still plausible that presenting ideal body types and diets can prompt its viewers to act upon the given procedures, the individuals showed no depreciating feelings towards themselves but rather motivating ones when presented with what they considered an attainable goal.24 Therefore, instead of the market brainwashing women to diet as argued in Zimmerman’s study,25 this experiment demonstrates that women could in fact be fully in control of the choices they make concerning their diets and bodies.

The intriguing question that seems to be argued by the two scholars here is similar to the “the chicken or the egg” dilemma. In other words, whether woman adopted an idealized body standard which caused markets to simply reflect, and create products that fit an increasing demand, or was it in fact the market that forced women to fit an idealized standard and the new definition of diet. Although both scholars make fair points, my research has shown that our primary focus shouldn’t be on “the chicken or the egg” dilemma, but rather on the fact that women and marketing have an interdependent relationship which created the feedback loop of diet hysteria. While it is hard to say exactly when perspectives on a healthy diet and dieting became distorted, it is reasonable to say that it was at some point in the 1950s after processed foods and diet pills were introduced, and a scientific understanding of nutrition forever changed the meaning of “diet” in America. It is impossible to debate who started the feedback loop. However, by being aware of the two leading variables in it, it is possible to learn from the mistakes within both spheres and employ a healthier definition of “diet” in the modern day.

Figure 1: Life Magazine, July 20, 1942.

Figure 2: Life Magazine, October 4, 1943.

Figure 3: Life Magazine, October 4, 1943.

Figure 4: Bar Graph on Frequency of Primary Focus in Articles and Advertisements on Nutrition from 1940s to 1970s.

Figure 5: Life Magazine, March 1, 1954.

Figure 6: Life Magazine Mar 1, 1954.

Figure 7: Life Magazine, Aug 4, 1952.

Figure 8: Life Magazine Mar 4, 1957.

Figure 9: Ebony Magazine, Oct 1971.

Figure 10: Ebony Magazine, Nov 1978.

Figure 11: Life Magazine, Jan 10, 1964.

1. Marika Tiggemann, “Media Influences on Body Image Development,” in Body Image a Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice, ed. by Thomas F. Cash (Guilford Press, 2012), 91–93.

2. “Diet Definition,” Cambridge Dictionary, Cambridge University Press.

3. Ibid.

4. “Your Grocer…Nutrition Headquarters,” Life July 20, 1942, 39.

5. “Good Diet Includes Protein, Vitamins, Minerals,” Life Oct 4, 1943, 101.

6. Ibid.

7. “More Milk is First Need of All The World’s Diet,” Life Oct 4, 1943, 104.

8. Angelina Not, “Data on Frequency in Primary Focus of Articles and Advertisements on Nutrition from the 1940s to 1970s,” May 3, 2019, Boston.

9. “ How to Cut Down on Salt – Cook Book Author Finds Lemons to be A Lifesaver,” LifeMar 1, 1954, 109.

10. “Because a Doctor put Tillie Lewis on a Diet – You Can Now Get Low-Calorie Foods as Delicious as High-Calorie Foods” LifeMar 1, 1954, 84.

11. Angelina Not, “Data on Articles and Advertisements on Nutrition,” May 3, 2019.

12. “Want To Lose Weight? – Listen to Hedy Lamarr,” LifeAug 4, 1952.

13. “Why Be Fat? Lose Weight this Quick Way,” LifeMar 4, 1957, 20.

14. “I took off 70 pounds and put on hot pants,” EbonyOct, 1971, 91.

15. “Your Grocer…Nutrition Headquarters,” LifeJuly 20, 1942, 39.

16. “Good Diet Includes Protein, Vitamins, Minerals,” LifeOct 4, 1943, 101.

17. “Doctor’s Program Featuring Crash-Burn Diet and Amazing Capsule Forces Your Body To Burn Away Fat As It Is,” Ebony, Nov, 1978, 155.

18. Ibid.

19. Frederick J. Zimmerman,“Using Marketing Muscle to Sell Fat: The Rise of Obesity in the Modern Economy,” Annual Review of Public Health 32.1 (2011): 285–306.

20. “Because a Doctor put Tillie Lewis on a Diet,” LifeMar 1, 1954, 84.

21. “The Amazing Success of Metrecal,” LifeJan 10, 1964, 56.

22. “I took off 70 pounds and put on hot pants,” EbonyOct, 1971, 91.

23. Silvia Knobloch-Westerwick and Joshua P. Romero,”Body Ideals in the Media: Perceived Attainability and Social Comparison Choices,” Media Psychology 14.1 (2011): 27-48.

24. Ibid.

25. Frederick J. Zimmerman,“Using Marketing Muscle to Sell Fat,” Annual Review of Public Health (2011).

This Post Has 0 Comments