Frida Kahlo’s boldness and confidence as a woman have always greatly inspired me. In a time when the politicization of feminism is a heavily debated topic, sharing Frida Kahlo’s stories is more important than ever. I began reading about Kahlo in high school, and her bravery immediately struck me. When hearing her stories, it seemed to me that Kahlo was so ahead of her time that she was independently creating a feminist movement. One thing that I find exceptionally admirable about Kahlo is that she never doubted herself. Kahlo attended the National Preparatory School, where she was only one of the 35 females in the male-dominated school. I love how outspoken, opinionated, and passionate about politics she was, especially when society expected her to do the complete opposite. As someone who cares deeply about their culture and heritage, I relate to Kahlo’s passion for persevering her culture while still aiming for social development

The most inspiring stories I’ve read about Kahlo were about her physical suffering and how she persevered through it. For example, she contracted polio when she was six, which led her right leg to grow significantly thinner than her left, leaving her with a limp. Her father encouraged her to participate in sports such as wrestling, soccer, and swimming to recover. Although males dominated such sports, it never held her back. I was also greatly inspired by Kahlo’s refusal to conform to society’s standards, as many girls in my age range and I often struggle with conforming to beauty standards. She defied the harsh beauty standards of the 1900s and was known for her bright colors, unibrow, and mustache. Kahlo owned her identity and individuality and was not afraid to challenge others, which is why her stories always resonated with me.

* * * * * * * * *

“They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality,”1 Frida Kahlo once remarked. The Mexican artist and feminist icon Kahlo grew up amid the Mexican Revolution, where her reality consisted of uprisings and national rebellion against corrupt dictator Porfirio Díaz Mori. The Mexican Revolution led to the emergence of newfound nationalism that inspired many artists, including Kahlo, to create a national identity through art. At a time of significant transformation, Kahlo utilized her artistic works to display her political beliefs and the Mexican Revolution’s effects. However, Kahlo’s personal life experiences also influenced her creative career. After a bus collision accident, Kahlo’s spine and pelvis were left fractured, and she was bedridden for nine months. The catastrophic accident left Kahlo with not only physical disabilities but mental trauma as well. Her sudden abundance of time in the hospital led her to paint her first self-portrait titled Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress. Furthermore, Kahlo’s turbulent relationship with her lover Diego Rivera often left her with feelings of betrayal, sadness, and instability. Although Kahlo’s physical trauma and volatile love life impacted her artistic works, Mexican politics had a more significant influence on her art.

The Mexican Revolution did not directly influence Kahlo’s artistic career; instead, it was the after-effects that shaped how she portrayed her national identity through her artworks. Although the Mexican Revolution ended in 1917, the consequences continued to unfold for decades. Kahlo’s adolescence in a politically turbulent environment gradually fueled and shaped her political views as an adult. In 1927, when Kahlo was just twenty years old, she joined the Mexican Communist Party and solidified her position as an activist for Socialism and Marxist ideas. In her diary, Kahlo expresses the sense of relief that accompanies her because of her Marxist views as she writes, “Today I’m in better company than for 20 years) I am a self and a Communist.”2 Furthermore, according to art history professor Janice Helland, the political climate in Mexico “was charged with cosmopolitan European ideologies, most prominently Marxism tempered with Mexican nationalism.”3 Along with the proliferation of Communist beliefs in Mexico was the dissemination and politicization of Mexican culture. After the revolution, Mexicans appreciated Mexican culture and heritage more than ever due to the emergence of an artistic revolution led by Frida Kahlo that focused on Mexican indigenous culture. Since the creative revolution emerged after the turbulent Mexican Revolution, such artistic expressions were acutely politicized.

The political climate in Mexico greatly inspired Frida Kahlo’s artistic work throughout the 1920s to 1940. In the self-portrait titled Marxism Will Give Health to The Sick (Figure 1), Khalo portrays how Marxism was able to heal the pain and suffering she endured in her life. The two large hands act as a metaphor for Marxism in which they hold and support Kahlo as she frees herself from her crutches. The two hands are portrayed to be divine as they descend from the sky, symbolizing Kahlo’s belief that Marxism wields divine-like powers, such as to heal those in suffering. Furthermore, a drawing of Karl Marx at the top right of the painting portrays him as a deity overlooking Kahlo with a calm and caring expression, symbolizing how she perceives the idea of Marxism. Besides, Marx’s hands strangling the American eagle, illustrating Kahlo’s stance on capitalism and the American economic system. Kahlo’s cinched leather corset paired with her traditional Mexican skirt illustrates her past struggles, injuries, and the restrictions imposed on her by capitalism. According to Helland, “Framed above her bed were pictures of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao.”4 From the framed images of Marxist icons in her bedroom, her affair with Russian Communist revolutionary Leon Trotsky, and her marriage with devout socialist Diego Rivera, Kahlo integrated politics in her everyday life.

Still, some scholars argue that Kahlo’s grueling physical history and unstable love life inspired her the most. According to Professor Minae Inahara in the book Encountering Pain: Hearing, seeing, speaking, Kahlo’s artworks portray her suffering, as she “was concerned with death and the vulnerability of her body.”5 From catching polio when she was six to her tragic bus accident where a pole went through her back and vagina, leading her to become infertile, Kahlo’s health was often at risk. Inahara adds, “Her work can be seen as a creative enquiry into her life, death, pain, disability and suffering, in which she is communicating the nature of living in/through a body such as hers.” In Kahlo’s diary she writes Rivera, “I ask you for violence, in the nonsense, and you, you give me grace, your light and your warmth.” By contrasting how she asks “for violence, in the nonsense” yet receives “light” and “warmth,” Kahlo is manifesting the tempestuousness of her and Rivera’s relationship.

Although Kahlo’s physical pain and stormy love life with Rivera played a significant role in her art career, her passionate activism and love for communism, especially during a time of remarkable uprisings in Mexico, seem to inspire Kahlo more. Kahlo is known for being a Surrealist; however, she expresses that her artwork serves a greater political purpose. In her diary she writes, “For the first time in my life my painting is trying to help in the line set down by the Party: REVOLUTIONARY REALISM. ”6 The artistic genre of revolutionary realism, also known as socialist realism, emerged from the Soviet Union during the 1930s. Revolutionary realism aims at illustrating communist ideologies through visual arts. By Kahlo characterizing her art under Revolutionary Realism, she expresses how she utilizes her artwork to portray the political ideologies that proliferated after the Mexican Revolution. When writing about one of her paintings, Kahlo says, “I want to transform it into something useful for the Communist revolutionary movement.” Throughout her artistic career, Kahlo strived to serve the Communist party and desired to play an active role in disseminating Socialist beliefs. By saying how she wants her art to be “useful” for the movement, she reveals her passion for her political environment and her self-enforced duty to be “useful” for the movement. Furthermore, Kahlo felt she had a responsibility to exhibit and disseminate her communist beliefs. According to Professor Liza Bakewell in her study titled “Frida Kahlo: A Contemporary Feminist Reading,” Kahlo “took to the streets in support of communist revolutionary movements, vociferously entering the political arena.”7 By describing how Kahlo was never afraid to display her communist beliefs with passion publicly, Bakewell builds upon the notion that Kahlo devoted a significant amount of her time to Communist activism.

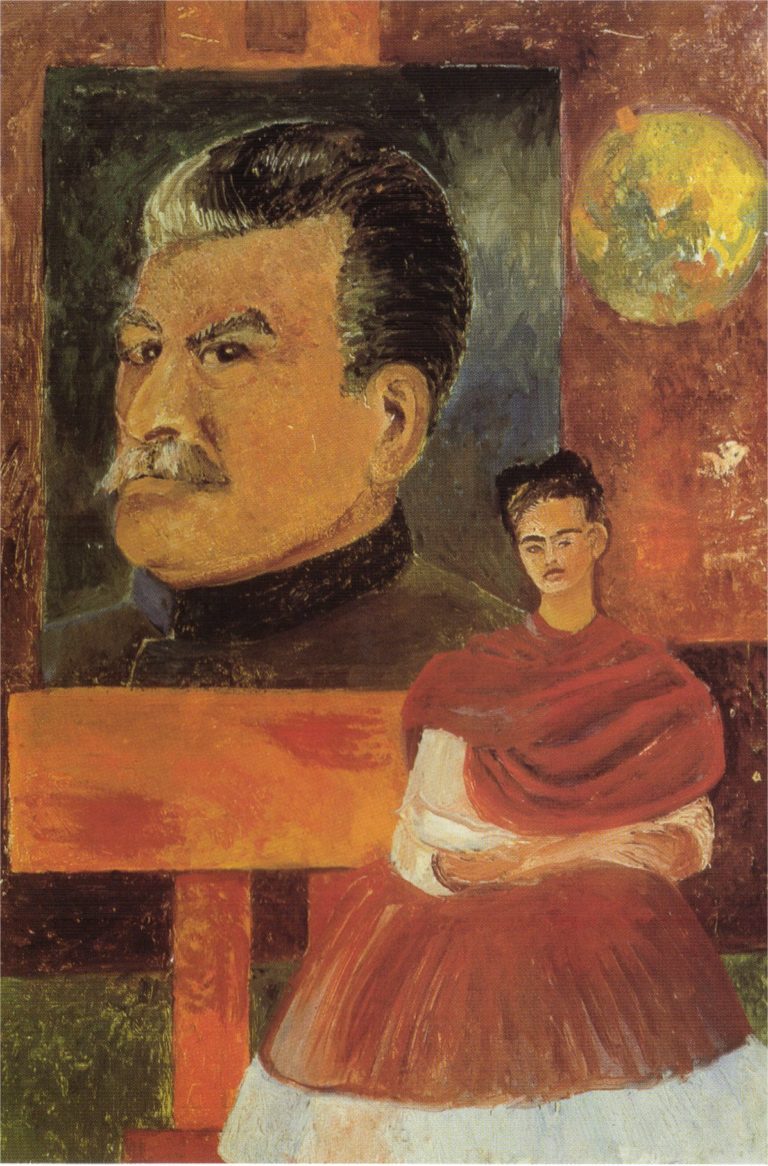

Kahlo particularly displays the techniques and themes of Revolutionary Realism theme in her painting titled Self-Portrait with Stalin (Figure 2). The painting contrasts with Marxism Will Give Health to The Sick in that it gives straight-forward expression to Khalo’s passion for Socialism. The painting is mostly devoted to Stalin, then a Communist icon, who shows a firm and authoritative facial expression. Kahlo utilizes contrasting dark colors for the Stalin painting and warm muted colors for herself and the background to emphasize his face. By devoting all of the attention to Stalin, Kahlo is symbolizing her devotion to the Communist movement. Similarly to the floating head of Karl Marx in Marxism Will Give Health to The Sick, Kahlo gives Stalin a godlike and lordly position. Self-Portrait with Stalin acts a political statement advocating for socialist ideologies as it contrasts Kahlo’s typical colorful and surrealist art.

Frida Kahlo’s oeuvre shows that artworks were inspired by all aspects of her environment. The three key elements surrounding her were her physical pain, her stormy love life, and her passionate political activism. However, Kahlo’s political endeavors were embedded in all three elements. Kahlo’s love life was inseparable from her political life. Kahlo’s lover, Rivera, was a communist activist known for social realist murals. Together, Kahlo and Rivera fought for a socialist world. In 1928, Rivera painted a mural titled The Arsenal (Figure 3), where he depicts Kahlo as a communist activist giving weapons to other social realists such as David Alfaro Siqueiros on the left. By including Kahlo in a mural that depicts his political beliefs, Rivera is illustrating how communism brought and bound them together. After the Mexican and Russian Revolutions, in the 1930s, Rivera and Kahlo began labeling themselves as Trotskyites and allowed the Trotskys to stay in their second home, “Casa Azul,” where Kahlo and Leon Trotsky had an affair.

Although Kahlo’s life experiences played a large role in her creative career, Kahlo often integrated her personal and political life. The consequences of the Mexican Revolution and the political climate it created acted as the most significant inspiration to Kahlo’s artworks.

Figure 1: Kahlo Frida, Marxism Will Give Health to The Sick, 1954, oil on Masonite, Mexico, Frida Kahlo Museum.

Figure 2: Kahlo Frida, Self-Portrait with Stalin, 1954, oil on Masonite, Mexico, Frida Kahlo Museum.

Figure 3: Rivera Diego, The Arsenal, 1928, oil on canvas, Mexico, Secretariat of Public Education Main Headquarters.

Bakewell, Liza. “Frida Kahlo: A Contemporary Feminist Reading.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 13, no. 3 (1993): 165. https://doi.org/10.2307/3346753.

“Diego Rivera, His Life and Art.” Diego Rivera – Paintings,Murals,Biography of Diego Rivera. Accessed April 8, 2021. https://www.diegorivera.org/.

Fuentes, Carlos, Frida Kahlo, and Sarah M. Lowe. The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait. New York, New York: H.N. Abrams, 2005.

Inahara, Minae. “The Art of Pain and Intersubjectivity in Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portraits.” Essay. In Encountering Pain: Hearing, Seeing, Speaking, 2–30. S.l.: UCL Press, 2021.

“Most Popular Paintings.” Frida Kahlo and Surrealism. Accessed April 7, 2021. https://www.fridakahlo.org/link.jsp.

Popova, Maria. “Frida Kahlo’s Politics.” Brain Pickings, July 5, 2017. https://www.brainpickings.org/2013/08/02/frida-kahlos-politics/.

1. “Most Popular Paintings,” Frida Kahlo and Surrealism, accessed April 7, 2021, https://www.fridakahlo.org/link.jsp.

2. Carlos Fuentes, Frida Kahlo, and Sarah M. Lowe, The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait (New York, New York: H.N. Abrams, 2005).

3. Janice Helland. “Aztec Imagery in Frida Kahlo’s Paintings: Indigenity and Political Commitment.” Woman’s Art Journal 11, no. 2 (1990): 8-13. Accessed April 7, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3690692.

4. Janice Helland. “Aztec Imagery in Frida Kahlo’s Paintings: Indigenity and Political Commitment.” Woman’s Art Journal 11, no. 2 (1990): 8-13. Accessed April 7, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3690692.

5. Minae Inahara, “The Art of Pain and Intersubjectivity in Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portraits,” in Encountering Pain: Hearing, Seeing, Speaking (S.l.: UCL PRESS, 2021), pp. 2-30.

6. Carlos Fuentes, Frida Kahlo, and Sarah M. Lowe, The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait (New York, New York: H.N. Abrams, 2005).

7. Liza Bakewell, “Frida Kahlo: A Contemporary Feminist Reading,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 13, no. 3 (1993): p. 165, https://doi.org/10.2307/3346753.