The degree of carnage and destruction, intensified by technological advances of a new industrial age, caused World War I to be a period of unprecedented conflict dating from 1914 to 1918 Generating catastrophic consequences such as economic turmoil, social discord and political strife, the war left millions of corpses in its wake. After the chaos and nationalistic fervor of the war besieged various nations, individuals suffered from a collective disappointment in humanity. The resulting disillusionment from the disastrous losses spurred a sense of nihilism or a radical sense of meaninglessness regarding life. Promoting this cynicism towards existence, a loose network of European artists, poets and intellectuals gathered at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich on February 5, 1916 to create a campaign that would combat a failed society led by corrupt systems and alter the face of popular culture. Key members Tristan Tzara and Hans Richter pondered how art could respond to the terrors of the Great War while breaking free of the shackles of tradition to create a new vision for the world. In Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, Paris and New York, these artists’ culmination of anti-war sentiment and rejection of cultural and intellectual conformity bore fruit in a nonsensical movement fostering revolt in the form of artistic chaos. From the disillusionment of the Great War, Dadaism emerged, a form of artistic anarchy that challenged the social, cultural and political values of the early 20th century.

The scale of warfare and loss generated by World War I left individuals disillusioned, struggling with their views about the human condition in a society of hostilities. In his musings on the psychological unrest permeating the European population, Sigmund Freud observed and communicated the transformation of human nature during total war. About six months after the onset of conflict, Freud wrote Reflections on War and Death in 1915, an essay regarding the principles of the community of mankind that are unsettled and damaged by war and of the institution of the civilized society, the state. Freud began his thesis by acknowledging the scope of destruction that has staggered even the “clearest intellectuals” of Europe.1 Freud shared the populace’s shattered expectations of a quick war and disheartened realization about the rational nature of humans when taken aback by the mass casualties and altered lifestyles of full-scale global warfare, the premise of early 20th century disillusionment. Turning the corner from the 19th century, an era of monumental advancements in technology and science, many individuals believed the new century would bring an epoch of progress and prosperity. However, the period of relative peace proved to be an illusion as advancements provided the means for humans’ utter self-destruction, bearing the reality of war with the likes never before encountered. Civilians were engrossed by total war, suffering drastic changes in daily life and struggling with their perspectives on war and death.

In regards to human nature, Freud believed that a discrepancy in the moral relations between nation and individual as outlined by the state in tandem with innate evil forces of human nature caused men to “commit acts of cruelty, treachery, deception, and brutality.”2 Gustave Le Bon, a French social psychologist who took great interest in the conduct of citizens during mass mobilization, takes Freud’s analysis a step further in The Psychology of the Great War by describing war as an elemental force that produces “new manifestations of the national mentality.”3 According to Le Bon, prolonged wars have the power to bring about changes in collective logic which force citizens to diverge from their superior instincts. In other words, a sense of mob mentality reveals the unpleasant truths regarding primitive human nature that Freud believed resides below the outwardly civilized nature of man. The power of this collective war mindset is so great, as Le Bon noted, that it may change a man “until he is unrecognizable” from his pre-war environment.4 It is therefore the impressions about the positive progress of man as a rational creature from which disillusionment sets in. With the reality of violent conflict, such as the brutality of military tactics of trench warfare, individuals were shocked by humanity’s barbarity and ferocity; this shattered the illusion of the enlightened man and bore mass psychological devastation.

The resulting world in which Freud’s and Le Bon’s individual finds himself helpless and estranged enabled the philosophy of nihilism to be a driving force of society. In his 1976 study, Nihilism in the Twentieth Century: A View from Here, Clyde L. Manschreck states that nihilism suggests a “mood of despair, a sense of emptiness and meaninglessness,” and a feeling that life resolves in the nothingness of death,5 a typical manner of responding to the devastation of warfare. Werner Haftmann writes in the postscript of Dada: Art and Anti-Art, that the war would inevitably prompt opposition as the growing disillusionment and critical sentiments of humanity fostered the growth “of every kind of revolt, resistance and protest.”6 Accordingly, from a flood of nihilistic rejections emerged a revolution that extended to every sphere of artistry: Dadaism or Dada. In the context of despair from the wreckage and squandering of war, disenchanted Dadaists strove to demonstrate that the world was without reason. Expressing their nihilism in absurdity, followers of Dada stood by “anti-reason, anti-aestheticism, anti-patriotism and anti-bourgeoisism.”7 Furthermore, Manschreck notes that the movement rejected all social and moral norms and declared that in a world of total war, chaos alone was real.8 Bolstered by these nihilistic sentiments, Dada would alter the artistic landscape and challenge the norms of a conformist society.

The Dadaists’ vision of the world as one of chaos reveals the paradoxical nature of Dada as the movement alone expressed itself in absurdity. A theorized origin story of the name Dada claims that artists Richard Huelsenbeck landed on the word by plunging a knife into a dictionary at random. The word “Dada” itself is a French colloquialism for a hobbyhorse and also echoes the garbled words of a baby; these suggestions of ridiculousness and childishness appealed to the founders who sought to establish a healthy distance between themselves and the sobriety of conventional society. It was also appreciated by the avowedly internationalist group that in other languages, the word contained similar nonsensical meanings like “yes yes” or carried no significance at all. Furthermore, the Dada manifesto claims that true Dadaists are against Dada, along with a mélange of other nonsensical provocations. Consistent with the expression of nihilism, co-founder and poet Tristan Tzara claimed that Dada draws no benefit: “like everything else in life, dada is useless.”9 However, he also claimed Dada seeks to confuse and jolt the norms of society. Despite resounding with contradictions, the movement of pandemonium managed to unify towards a shared ideal.

Dada was not so much a style or form of art than a protest movement driven by an anti-establishment platform. In fact, Tzara noted that the beginnings of Dada were not ones of art, “but of disgust.”10 In Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, Professor Michael Kelly examines where Dadaists placed their collaborative efforts. Kelly notes that Dada represented for the creators a way to express “their profound sense of rage and grief” over the humiliation and suffering of mankind as demonstrated by the evolving war.11 In a related study, “Dadaism and the Peace Differend,” Oliver P. Richmond offers a similar account, suggesting that Dadaists sought to dissolve the confines of an overly rational world and form a new social order to “cure the madness of the age” as demonstrated by the writings of Freud and Le Bon .12 He also makes it evident that many Dadaists were pacifists, or at least anti-war.13As a result, the movement had a twofold objective: to help put an end to the horrors of warfare and to vent frustration with the nationalist conventions that led to it. Despite this shared perspective among Dadaists, it is notable that, keeping to its paradoxical nature, Dada made for a protean movement as they were opposed to forms of group leadership or guiding ideologies.

As noted earlier, in a conventional approach to Dada, the movement lacked any unifying style. Dafydd Jones, author of Dada 1916 in Theory: Practices of Critical Resistance, claims that style “as a signal of unity, completion and identity” is simply not present.14 Visual Dada was connected through themes and concepts, rather than stylistic elements, which strove to humiliate conventional artistry. As a result, Dada art was referred to as “anti-art,” a term coined by co-founder Hans Richter due to its rejection of what Richmond claims to be the “stifling conventions and formalism” that inhibited chance, development and innovation.15 Kelly observes that these concepts drew upon elements of irrationality to confront established modes of thinking and shake the complacency of fellow individuals in society.16 Consequently, anti-art was not meant to be aesthetically pleasing as it was anti-beauty and anti-tradition. Dada often came to fruition in the form of collage style posters which included bold texts and typography; photomontages which reworked photos to create an entirely new piece; assemblages which created a three-dimensional sculptural collage of objects; and readymades which expressed an existing object as a wonderous piece of art. Manschreck points out that to “express chance, purposelessness and irrationality,” Dadaists simply dropped objects and paint into their various creations.17 The absurdity of visual Dada challenged the conformity of traditions of conventional society.

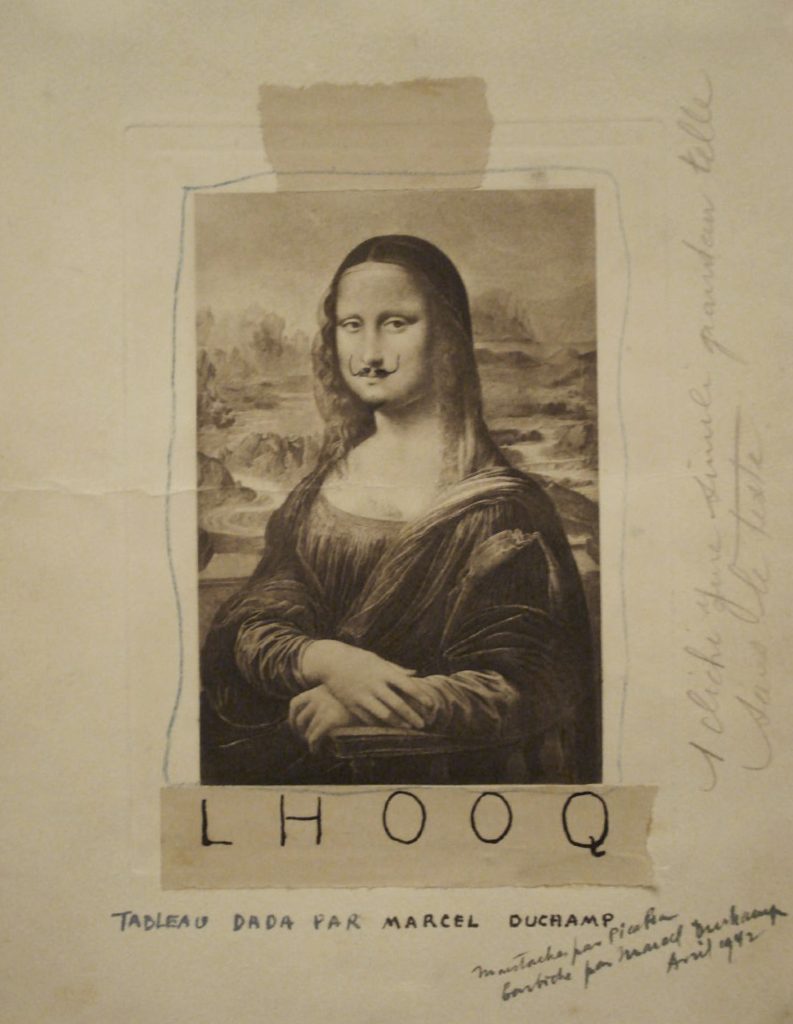

Exiled in New York during the war, French artist Marcel Duchamp soared to rare heights of innovation and defiance in 1917 with his readymade called “Fountain.” The sculpture was a standard white porcelain urinal taken from a factory shelf signed with the pseudonym R. Mutt. Duchamp’s exhibit simply consisted of the urinal placed atop a pedestal (Figure 1). The sculpture was banned from exhibition as members of the board believed a sanitary utility could not possibly resemble artwork. However, by signing the object, Duchamp declared it to be a work of mastery and challenged the established ideals of what could be considered art. “Fountain” declared a new democracy for artists in which they could widen their frame of reference when drawing meaning from the world and implementing it in art. In another cause for outrage, Duchamp’s “L.H.O.O.Q.” parodied the Mona Lisa by sketching facial hair onto a postcard of the Renaissance masterpiece. The abbreviation, when read aloud in French, sounds like the phrase “elle a chaud au cul” which, when translated in English, claims “she has a hot ass” (Figure 2). Duchamp created several other readymades including “Bottle Rack,” and “Bicycle Wheel” which, through absurdity, continued to challenge the traditional modes of artistry.

At the end of the Great War, the movement became particularly active in Germany; however, Dada in this region took on a more political essence. Germany was left to suffer with devastating economic turmoil as a result of the Treaty of Versailles and deal with a political disorder due to a power struggle of governance. The chaos of post-war destruction reinvigorated the nihilist sentiment as produced by Freud and Le Bon’s disillusionment among man and enabled new radical approaches of opposition. Berlin, especially, was a melting-pot of economic and political strife in which Dada was “less artistic in its outlook [and] more confrontational and anarchic,” as noted by Jed Rasula in Destruction Was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the Twentieth Century.18 In this climate, Dadaists focused mainly on social and political issues to criticize the new post-war reality and pointed the weapons of provocation and confrontation which often landed them in trouble with authorities. Through the creation of photomontages, artists delivered strident political satire complete with disparaging commentary. This technique comprised of a collage of text and photographs cut from magazines and newspapers. Using imagery and text from the media as a vehicle of criticism, they targeted political figures and warfare and also took on an air of authority as the artist connected their criticisms with the real world by incorporating excerpts and cuttings from the press.

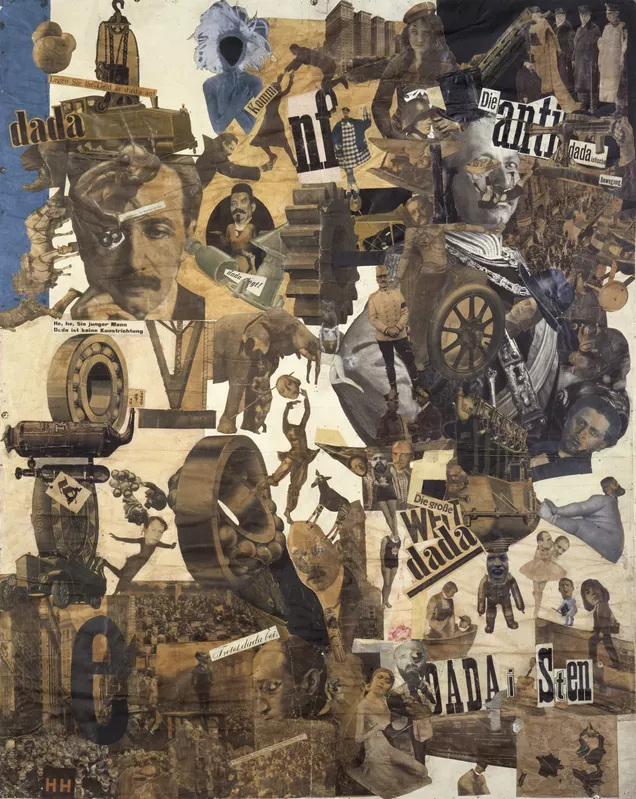

Created in 1919, Hannah Hoch’s “Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany” (Figure 3) is a notable example of German photomontage in which the artist captured the post-war chaos along with the cultural and political fragmentation of the newly formed Weimar Republic which faced numerous issues from the onset of its position of power. Upon close observation of the cacophony of images included in the collage, a cross-section of Germany’s political and cultural contexts come into view. Around the work are pictures of sporadic machinery, text fragments, maps, buildings, crowds, dancing women, and disembodied heads. The densely populated photomontage featured Hoch’s rejection of the German government and her criticism of gender issues. Like the collage itself, Hoch was able to present a layered and complex argument about the tumultuous period.

Another work criticizing the post-war chaos, Raoul Hausmann’s “Spirit of Our Time” (Figure 4) was a sculptural assemblage that served as a metaphor for the inability of establishment to produce the necessary changes to reform a better Germany. This blockhead of a hat maker’s mannequin illustrates an individual having no more capabilities than the ones which have been placed on the outside of his skull; despite the chance of objects, his brain remains empty. Glued to the dummy head are a ruler and tape measure, a beaker issued to German soldiers during the Great War, a jewelry box, the brass knob of a camera, a pocket watch and an old nail purse. The eyes of the sculpture are left deliberately blank in order to convey the subject as a blind, narrow-minded automaton who is incapable of a creative thought.

Relatively unstable and chaotic in nature without a central hierarchy or set of rules, Dadaism dissolved and gave way to Surrealism in 1924, an established, solidified movement focusing on positive expression and tapping into the “dream world” of the subliminal mind. Despite this cession of influence, Dada’s significance continued through the decades, impacting and paving the way for modern art. The absurdity of Dada transformed the very definition of art, allowing for unbound creativity in contemporary works that continues to expand today. From its inception, the nonsensical movement established a platform fueled by angst and anti-war sentiment that targeted a corrupt society and its repressive norms. This raises the question, had post-war disillusion not fostered the anarchy of Dada, what would become of art today? Furthermore, would pieces such as abstract sculpture or collages ever surface? Perhaps the modern artist would have an entirely new aesthetic of expression. Dadaism, in its ridiculousness and chaos, altered the rules of artistry and set the precedent for art as it is known today.

Figure 1: “Fountain” 1917, Marcel Duchamp, Photographed by Alfred Stieglitz

Figure 1: “Fountain” 1917, Marcel Duchamp, Photographed by Alfred Stieglitz

Figure 2: “L.H.O.O.Q.” 1919 (Playing Card Reproduction Mounted on Paper, 1965), Marcel Duchamp

Figure 2: “L.H.O.O.Q.” 1919 (Playing Card Reproduction Mounted on Paper, 1965), Marcel Duchamp

Figure 3: “Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany” 1919, Hannah Hoch

Figure 3: “Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany” 1919, Hannah Hoch

Figure 4: “The Spirit of Our Time” 1919, Raoul Hausmann

Figure 4: “The Spirit of Our Time” 1919, Raoul Hausmann

1. Sigmund Freud, “Sigmund Freud: Thoughts for the Times on War and Death (1915),” trans. A. A. Brill and Alfred B. Kuttner, in Ideas and Identity in Western Thought: Readings in Politics, Economics, Society, Law and War, ed. Michael Holm (San Diego: Cognella, 2020), 284.

2. Freud, 287.

3. Gustave Le Bon, “Gustave Le Bon: The Psychology of the Great War (1916),” trans. E. Andrews, in Ideas and Identity in Western Thought: Readings in Politics, Economics, Society, Law and War, ed. Michael Holm (San Diego: Cognella, 2020), 291.

4. Le Bon, 291.

5. Clyde L. Manschreck, “Nihilism in the Twentieth Century: A View from Here,” Church History 45, no. 1 (March 1976): 86, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3164567?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents.

6. David Britt, Werner Haftmann, Hans Richter and Michael White, Dada: Art and Anti-art (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2016), 261.

7. Manschreck, “Nihilism in the Twentieth Century: A View from Here,” 89.

8. Manschreck, 89.

9. Manschreck, 89.

10. William Rubin, Dada, Surrealism and Their Heritage (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1968), 78.

11. Michael Kelly, Encyclopedia of Aesthetics (London: Oxford University Press, 2014), 26.

12. Oliver P. Richmond, “Dadaism and the Peace Differend,” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 32, no. 4 (2007): 451, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/stable/40645230?seq=8#metadata_info_tab_contents.

13. Richmond, 451-452.

14. Dafydd Jones, Dada 1916 in Theory: Practices of Critical Resistance (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2014), 7-8.

15. Oliver P. Richmond, “Dadaism and the Peace Differend,” 448.

16. Michael Kelly, Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, 26.

17. Manschreck, “Nihilism in the Twentieth Century: A View from Here,” 89.

18. Jed Rasula, Destruction Was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the Twentieth Century (Basic Books, 2015), xiii.