Formal “Pitch” to Professor Sweeting

The College of General Studies Humanities 104 course covers several art movements, works of literature, musical pieces, and key themes. In the course, students grapple with ideas such as the role of nature in our industrialized world, the hierarchical order of social classes, nostalgia developed throughout childhood, and the way in which our individual personal being can also be political. The Impressionist art movement that began in Paris, France in the late 1800s emphasized course themes by calling attention to the growing impacts of industrialization on both rural and urban areas, while often depicting nontraditional subjects of ordinary people and scenes of everyday Parisian life. Founding Impressionist artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) directly protested the accepted artistic practices of Paris at the time that revolved around the French Academy and its government sponsored exhibitions called Salons. The art in these exhibits often only portrayed significant historical events and the upper class, but in complete contrast, the Impressionists aimed to depict relatable, short-lasting moments of the lives of both countryside and city individuals in the middle class. The most common settings tended to be those that involved leisure time: activities in the countryside on the outskirts of Paris or any of the numerous cafes and restaurants that had grown to be a huge part of Parisian culture. Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s painting The Skiff (La Yole) expresses the Impressionists’ fascination with how the countryside interacts with urbanization and can be connected to poet William Wordsworth’s contemplation of experiencing in the moment versus later in reflection. Edouard Manet’s painting At the Cafe, in contrast, depicts the Impressionist interest in city cafe scenes through multiple representations of different social classes, and reflects the consumer paradise and adventurous nature of Paris in Guy de Maupassant’s short stories. Both paintings, when combined with course reading materials, create a complex picture of Paris in the late 1800s that relate to course questions about the role of the natural world in an industrialized society and the changes in representation of traditionally underrepresented groups in a progressing society.

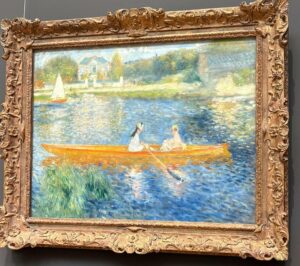

Renoir’s The Skiff (La Yole) from 1879-80 embodies both Impressionist stylistic art form and easy access to the countryside due to new rail lines and transportation. The painting itself (see image to the right) is oil on canvas, and has been on display at London, England’s National Gallery since it was acquired in 1982. The setting is most likely of the River Seine near the town of Chatou, but the specific location has never been confirmed.1 From a general perspective, the painting shows two fashionably dressed women, rowing in a small skiff along the river, and a railway bridge that is almost out of view along the skyline above the treetops. The common activity is painted in the Impressionists’ signature style of bright colors and light subject matter with few, less intense shadows. The brushstrokes in the foreground are bold and noticeable, but they become smoother and create a blur effect as they continue into the background. Renoir’s specific touches are the way in which the light reflects and “shimmers” across the water, and the conscious choice to make the skiff a bright orange, contrasting the light and deep blues of the surrounding river. He played off new advancements in the understanding of complimentary colors.2

Renoir’s The Skiff (La Yole) from 1879-80 embodies both Impressionist stylistic art form and easy access to the countryside due to new rail lines and transportation. The painting itself (see image to the right) is oil on canvas, and has been on display at London, England’s National Gallery since it was acquired in 1982. The setting is most likely of the River Seine near the town of Chatou, but the specific location has never been confirmed.1 From a general perspective, the painting shows two fashionably dressed women, rowing in a small skiff along the river, and a railway bridge that is almost out of view along the skyline above the treetops. The common activity is painted in the Impressionists’ signature style of bright colors and light subject matter with few, less intense shadows. The brushstrokes in the foreground are bold and noticeable, but they become smoother and create a blur effect as they continue into the background. Renoir’s specific touches are the way in which the light reflects and “shimmers” across the water, and the conscious choice to make the skiff a bright orange, contrasting the light and deep blues of the surrounding river. He played off new advancements in the understanding of complimentary colors.2

The Skiff (La Yole) follows the Impressionist trend to depict the movement of city-goers to the countryside due to the increasing accessibility of transportation. These areas provided busy Parisians a stark contrast to the quick-paced and overpopulated city. Instead, they could engage in relaxing activities surrounded by the peace and serenity of the natural world. William Wordsworth (1770-1850), an English Romantic poet, explored the role of nature and its virtue in comparison to the slums of London in his time. To Wordsworth, nature had a certain healing or growing quality that allowed one to slow down and contemplate. The city, on the other hand, was often too fast-paced to live in the moment and take in one’s surroundings.3 Wordsworth extremely valued the act of experiencing: in his poem, “Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802,” he asserted a sense of specificity in the moment by making the date a part of his title and he created a scene that evokes all five senses when read. In this way, Wordsworth wrote as he was experiencing a London sunrise, on the bridge itself, instead of later on, from a removed setting.4 Similarly to this, Impressionist artists often created nature paintings outside, in the environment in which they occurred, rather than the traditional practice of using studio rooms.5 For Wordsworth and the Impressionists, the short moments–immersed in the natural world and removed from urban cities like London or Paris–had a new level of intimacy and personalization to relay the individual experience.

Although Wordsworth and the Impressionists lived almost 200 years ago, the fleeting role of the natural world is not a struggle that is lost to us today. They may have been perplexed by trying to balance steam engine trains, electricity, and eventually the combustion engine that would be used in automobiles, but today we have become even more distanced from the rural and natural parts of the world around us. The internet and its associated forms of entertainment such as movies, video games, and social media only push us further away from the outdoors and traditional activities that took place in those environments. Impressionist paintings like Renoir’s The Skiff (La Yole) force us to recognize that missing connection with the natural world that is often overlooked in the convenience of the forms of entertainment present today that can be acquired by simply pressing a few buttons on any kind of portable, mobile device.

Manet’s At the Café from 1878 embodies the other side of preferred Impressionist setting and subject matter: cafe and pub-style community gatherings in Paris. This oil painting on canvas hangs at the National Gallery among the previous The Skiff (La Yole) and other influential impressionist pieces (see image to the right). The painting was originally a part of a larger piece that was composed of both At the Café and another segment named Corner at a Café Concert, but Manet chose to split both segments into their own paintings in 1878. The selected half, At the Café, shows Parisians enjoying a concert (not pictured, but more apparent in the other half) with a few pints of beer at one of the many local brasseries. These spaces provided friends with drinks and entertainment that made meaningful quality time out of leisure time away from work. The man in the center of the painting has been identified as lithographer Henri Guérard and the woman he is leaning on to his right is actress Ellen Andrée, who happened to be a common model for many of the Impressionists.6 Manet uses similar brushstroke techniques as Renoir, which clearly shows the deliberate direction of the strokes without much blending. Manet used a much darker color palette than Renoir at points, particularly through using more shadows and depth to illustrate the ambiance of the brasserie. The golden orange of the beer in the pints contrasts the light blue paint on the walls; Manet was influenced by the same laws of complementary colors as Renoir.

Manet’s At the Café from 1878 embodies the other side of preferred Impressionist setting and subject matter: cafe and pub-style community gatherings in Paris. This oil painting on canvas hangs at the National Gallery among the previous The Skiff (La Yole) and other influential impressionist pieces (see image to the right). The painting was originally a part of a larger piece that was composed of both At the Café and another segment named Corner at a Café Concert, but Manet chose to split both segments into their own paintings in 1878. The selected half, At the Café, shows Parisians enjoying a concert (not pictured, but more apparent in the other half) with a few pints of beer at one of the many local brasseries. These spaces provided friends with drinks and entertainment that made meaningful quality time out of leisure time away from work. The man in the center of the painting has been identified as lithographer Henri Guérard and the woman he is leaning on to his right is actress Ellen Andrée, who happened to be a common model for many of the Impressionists.6 Manet uses similar brushstroke techniques as Renoir, which clearly shows the deliberate direction of the strokes without much blending. Manet used a much darker color palette than Renoir at points, particularly through using more shadows and depth to illustrate the ambiance of the brasserie. The golden orange of the beer in the pints contrasts the light blue paint on the walls; Manet was influenced by the same laws of complementary colors as Renoir.

The painting, from a glance, probably seems to only convey the conversations of friends and the enjoyment of the lively environment of Parisian brasseries. Despite this general first impression, Manet works in a deeper symbolism beyond what one first notices: the top hat on Guérard represents the dress of the upper class, whereas the bowler hat and simple dress on Andrée is typical of the bourgeoisie. If one looks closely, the working class also makes an appearance through the waiter in the background of the painting who is wearing a traditional blue apron or smock.7 This challenged the portraits and scenes from the Salon exhibitions mentioned earlier that likely would never have acknowledged the working or middle classes. Manet’s inclusion of many social classes formed a sense of unity and progress present in Parisian society that helped contribute to the collective community aspect.

Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893), a French author who is considered to be the master of short stories, wrote a series of short stories related to 19th century Parisian life. His stories like “A Parisian Affair” express parallel themes to Manet’s At the Café but go into more depth about the adventurous and daring environment that Paris fosters with its night and consumer scene. Maupassant focuses particularly on the way in which women, who were traditionally limited to extremely restricted roles in society, could go to Paris and let go of some of those social norms.8 Like Manet, Maupassant created space for individuals who were not traditionally represented. But whereas the painter did so by clearly depicting members of different social classes, Maupassant told the stories of women which had previously been unwritten. The economic and urban growth did not only affect consumerism and cafe culture but also fostered an environment of social change. Both the expanded mingling between socioeconomic classes and a greater presence of women in everyday life outside of the home were forces at the forefront of the altered status quo. The modern liberal society of the West has made abundant progress towards positive social change and securing rights for marginalized groups, but it is still important to understand where we have come from and which of those challenges we still face today.

Personal Conclusion

In my opinion, humanities courses are not meant to be stagnant. History plays an important part in providing context for what we learn, as I suggested in relation to social change, but it is not meant to feel stuck in time. The history that we capitalize upon in class should evoke modern-day questions that relate to the world around us. For example, with Guy de Maupassant’s short stories, I view them as relating to 21st century America despite being created in 19th century France. The theme of the representation of women and which rights they do or do not have is still of the utmost relevance today. Our course already has so many meaningful pieces of art, music, and literature that push the idea of history playing a huge role in the world today. Despite this, I found that the historical context and physical content of both The Skiff (La Yole) and At the Café made me think of certain questions and avenues that I hadn’t thought of before. These are not pieces of art that can be taken at face value without any analysis, as is especially true for the class element related to Manet’s painting. I believe in the process of deep thinking that comes with historically and socially nuanced pieces such as the two that I chose. In a world where technology and tools such as artificial intelligence are changing–arguably for the worse–the process and concept of education, these nuanced moments are the ones that will force students to think individually in a world full of growing conformity.

De Maupassant, Guy. A Parisian Affair and Other Stories. London: Penguin Classics, 2004.

Tate Britain & Modern. “Art Term: Impressionism.” Accessed June 21, 2025. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/i/impressionism.

The National Gallery. “About the Work: At the Café.” Accessed June 21, 2025. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/edouard-manet-at-the-cafe.

The National Gallery. “About the Work: The Skiff (La Yole).” Accessed June 21, 2025. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/pierre-auguste-renoir-the-skiff-la-yole.

William Wordsworth. “Composed upon Westminster Abbey Bridge, September 3, 1802.” In Norton Anthology of Western Literature. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014.

“William Wordsworth.” In Norton Anthology of Western Literature. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014.

1. “About the Work: The Skiff (La Yole),” The National Gallery, accessed June 21, 2025, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/pierre-auguste-renoir-the-skiff-la-yole.

2. “About the Work: The Skiff (La Yole),” The National Gallery.

3. “William Wordsworth,” in Norton Anthology of Western Literature (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), 541-544.

4. William Wordsworth, “Composed upon Westminster Abbey Bridge, September 3, 1802,” in Norton Anthology of Western Literature (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), 554.

5. “Art Term: Impressionism,” Tate Britain & Modern, accessed June 21, 2025, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/i/impressionism.

6. “About the Work: At the Café,” The National Gallery, accessed June 21, 2025, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/edouard-manet-at-the-cafe.

7. The National Gallery, Art Piece Description (Plaque.)

8. Guy de Maupassant, A Parisian Affair and Other Stories (London: Penguin Classics, 2004).

Newspapers. Blogs. Books. Magazines. Radio. Television. Mass media permeates every aspect of existence, from the ads we quickly glance at while walking down the street to the cat videos we watch on Instagram. Mass media is defined as “forms of communication designed to reach many people,” and it is an undeniable and unavoidable part of modern life (“Mass Media”). How does mass media impact people? How is it a force for both good and bad? I will analyze the novella A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, the artwork Marilyn Diptych by Andy Warhol, and the sculpture Babel by Cildo Meireless to explore the nuances of mass media and argue that it functions as both an aid and a hindrance to humans due to its permanent presence in our lives.

Upon first walking into the room in the Tate Modern where Cildo Meireless’ Babel is displayed (pictured above), I was surrounded by dim lighting and empty space. As my eyes adjusted, my view became swallowed by the towering structure in front of me. Made in 2001, the behemoth of Babel consists of hundreds of radios stacked on top of one another, each tuned to a different station (“Cildo Meireless”). The lines are straight and geometrical on the bottom and rounded on the middle and top of the piece. The frenzy of noise the sculpture plays is overwhelming and slightly painful to the ears, as dozens of voices, songs, and news broadcasts play simultaneously. In terms of materials, the radios’ ages correspond to the sculpture’s height chronologically, as large radios from the 1920s form the base and small modern radios model the top, narrowing the piece and emphasizing its lofty form (“Cildo Meireless”).

Babel is an ode to the confusion and anomie experienced by consumers of mass media. The word “Babel” refers to both the “babbling” of voices and songs coming from the radios and the Tower of Babel, a biblical story in which God is displeased with a tower humans build to reach the heavens (“Tower of Babel”). God confuses the builders of the tower by making them speak different languages, thereby halting the structure’s completion (“Tower of Babel”). This echoes how mass media constantly pushes new and conflicting information onto consumers, akin to a mental tug of war. The height of the sculpture symbolizes the colossal presence of mass media in human life, and the darkness of the room expresses how mass media, such as social media, television, and books, can act as a welcome escape from the bleakness that everyday existence can be. Similar to the fever dream of voices weaving in and out of my ears when witnessing Babel, it is hard to tell truth from lie and useful from useless when being inundated with so much knowledge. Alongside confusion, this can cause feelings of isolation due to comparison with others’ carefully curated virtual lives. I am reminded of my struggles with synthesizing all the different, unending information provided by social media, from what is healthy to eat and whether a friendship is worth keeping. I am also drawn to reflect on how London has helped me step back from the escapism mass media provides and experience life beyond a screen. I feel less overwhelmed and more in tune with the present because I have less time to agonize over the news and compare myself to celebrities on television. This is not to say that mass media is all bad, but rather to point out its adverse effects, which almost everything has when consumed in extreme, one might say, towering amounts.

Andy Warhol’s 1962 screenprint Marilyn Diptych introduces how mass media commodifies people (“Marilyn Diptych”). Warhol experimented with the technique of screen printing following the untimely death of Hollywood star Marilyn Monroe, the subject of the piece. The composition is formed by a halved rectangle made up of a grid of reproduced headshots of Monroe. The left side is vibrant and colorful, consisting of orange, blue, yellow, and light purple, while the right side contrasts with the left by using only black and white. On the right, Monroe is faded and blotted out, while on the left, her image is clear and unobstructed. The lines and shapes of the piece are straight and geometrical. Monroe’s face reads an enigmatic expression, and the screen printing technique makes her appear flat and muted.

Marilyn Diptych not only explores the pressures of celebrity culture and Monroe’s legacy after her death, but also how mass media reduces celebrities and people to commodified “objects” devoid of humanity or personality. The Pop Art style employed by Warhol in his artwork was characterized by depictions of products, advertisements, Hollywood figures, and other elements of popular culture. Monroe is the perfect subject for a Pop Art piece, as she serves as both a symbol of Hollywood sex appeal and as an iconic, idealized figure beloved, yet objectified and dehumanized, by the public. Similar to mass media’s ability to extract value from things and turn them into commodities, Warhol’s use of repeated images of Monroe commercializes her, likening her to a product on a shelf rather than a human being. When new products, ideas, and people are presented in a mass, emotionless format to the public, things begin to lose their value and take on an “advertised” quality, as Monroe does. Celebrities are people who struggle with personal problems, as represented by the right side of the piece. When they are only presented as the left side, starlit and perfect, they lose their humanity and transform into “things” rather than humans.

Conversely, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol teaches the importance of human connection and compassion. In A Christmas Carol, Scrooge is the epitome of a classical liberal, looking down upon the working class and blaming them for their station in life. Before his transformation, he states that “‘If [the poor] would rather die, they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.’” Later, he meets the emaciated and filthy children Ignorance and Want, whom he is appalled by. When Scrooge questions why the children are in such a state, the Spirit of Christmas Present points out his hypocrisy, asking, “‘Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?’” A Christmas Carol is a ghost story about a man who changes for the better, but more importantly, a critique of social inequality and unfair attitudes towards the impoverished. Ignorance and Want symbolize the failures of society and the lack of social safety nets in the Victorian era. At the same time, Scrooge represents the wealthy, prevailing classical liberal viewpoint that the poor deserve their circumstances. Despite this, the story shows optimism and the potential for change. Scrooge sees the cruelty of his mindset and devotes Christmas to good deeds, becoming “As good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew.”

A Christmas Carol is an example of mass media’s positive impact due to its progressive messaging and immense popularity. Upon its release in 1843, it sold out in less than a week and has continued to be popular into the 21st century (Beete). When going about London, Dickens’ lessons apply all the more. It is impossible not to see unhoused people sitting on the sidewalks or lying in the Tube stations, and reading A Christmas Carol has helped me become more aware of my judgments and biases. As previously argued, mass media can cause harm, but it can also help consumers question the status quo and engage in essential critical thinking. By critiquing prevailing opinions of its time, A Christmas Carol teaches vital lessons about humanity and compassion, leaving its readers better off than they were before.

Babel, Marilyn Diptych, and A Christmas Carol all convey the message that mass media has the power to influence its consumers. My time thus far in London, reading, and observation of these pieces have drawn me to analyze how mass media influences my ideas and perceptions of myself and the world. In reflecting on my thoughts, I have become more self-aware, which I believe is the first step to becoming a better person and undoing any harm caused by my constant consumption. I am left pondering how I would feel in a world with less mass media. How would I be different? How would I be the same? Would less mass media leave the world in a better or worse state?

Beete, Paulette. “Ten Things to Know about Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.” National Endowment for the Arts, www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2020/ten-things-know-about-charles-dickens-christmas-carol. Accessed 21 June 2025.

Cildo, Meireless. Babel. 2001, Tate Modern, London. Sculpture.

“Cildo Meireless,” Tate Modern, https://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern/display/media-networks/cildo-meireles.

Accessed 21st June 2025.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Chapman & Hall, 1843. The Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/46/46-h/46-h.htm. Accessed 21st June 2025.

“Marilyn Diptych.” Tate Modern, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/warhol-marilyn-diptych-t03093. Accessed 21st

June 2025.

“Mass Media.” Merriam Webster, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tower-of-Babel. Accessed 21st June 2025.

“Tower of Babel.” Britannica, 19 May 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tower-of-Babel. Accessed 21st June 2025.

Warhol, Andy. Marilyn Diptych. 1962, Tate Modern, London. Silkscreen painting.

“Spinning or casting?”

“What’s the difference?” I replied.

“What do you think about these lures? Should I get this spray for us? They say it’s supposed to attract larger ones.”

“Do you know what we actually need from here?”

“No.”

I’ve heard many say that there are moments in life that really make you aware of just exactly where you are. I had always thought that fabled moments like that are supposed to be more grandiose than standing in a Bass Pro Shop on a Thursday evening. Nevertheless, there I was, standing in the middle of the aisle with my dad (both of us clearly out of our depths) scrambling to get any piece of fishing gear that looked like it would be useful or that we could vaguely remember seeing in any TikTok videos we had shared with each other on the topic.

However, while he was dead focused on the myriad of aquatic paraphernalia laid out in front of us, all of my attention was centered on him. Why had this man, who spent his days either working all around computers or in the bustling cities of Southern California, all of a sudden gained such an interest in something as alien to him as fishing?

The more I thought about it, the more I began to notice it wasn’t just him. All around me, more and more people seemed to be turning away from the noise of modern life, drawn instead to slower rhythms, quieter spaces, and moments of contact with the natural world. I started wondering: what’s behind this pull? Why, after generations of racing toward “progress” and the amenities it’s brought with it, do we feel the need to turn back? Why turn back to the forests? Why turn back to the mountains? Why make a return to the natural world?

As time passed, my dad and I went on several trips to the various lakes and prime coastal waters of California. During this time, I always kept my questions in the back of my mind and slowly, I began to realize that what drew my dad into fishing wasn’t just filling out a new hobby, but the feeling it gave him. With him, I had experienced the stillness of the water, the early morning light, and the patience the sport required. It was in stark contrast to the noise and pace of his daily life. And he wasn’t alone. Across research and lived experience, there seems to be a growing recognition that nature actually offers something many of us have been missing, not just physically, but emotionally and psychologically.

Studies into the psychological effects of nature have shown how short periods of immersion in nature can foster feelings of awe, contentment and a sort of, “mental restoration.”1 One such research study was conducted by scientists Matthew T. Ballew and Allen M. Omoto, where they compared individuals who spent just fifteen minutes in a natural setting with those who remained in an artificial, “built” environment, and the difference was remarkable.2 Those surrounded by nature reported a greater sense of well-being and emotional calm.3 What strikes me is how little time it took for participants to feel this sentiment. Achieving the feeling didn’t require some grand, week-long retreat; it offered peace in minutes. This suggests something fundamental, even primal, about our connection to the natural world. Is this rapid, “mental restoration,” gained because it’s how we are meant to be?

In another light, could this idea be tied to our current culture? American author, Richard Louv, coined the term, “nature-deficit disorder,” which describes the cognitive, emotional and physical consequences of being alienated from the natural world.4 It’s his sentiment that Columbia Climate School student Renee Cho shares when she states how higher rates of stress, obesity, ADHD and asthma, are all linked to our increasingly modern lifestyles.5 Now I know it’s no secret that most people are spending less time outdoors, but what was less obvious to me was the real consequences that come with this lifestyle. The further we move away from green spaces, the more we seem to suffer. I was under the impression that being outdoors was just for enjoyment, but with all these ailments that come with being away from it for too long, is there something within us that needs it?

A uniquely modern angle on this issue is the growing and urgent threat of environmental collapse. Our emotional distance from the natural world, combined with this threat, gave rise to what psychiatrist Craigan Usher calls, “eco-anxiety.”6 Especially among younger generations, there is a growing sense of dread about the future of our planet.7 Climate change, deforestation, loss of biodiversity. In years past people didn’t think too deeply about these issues, but now they’re real, they’re personal.8 These issues shape how we think about having children, where we live, and even how we envision our own futures.9 Usher writes that many young people feel overwhelmed by the environmental damage they’ve inherited and how they feel powerless to fix it.10 And what has this resulted in? A kind of existential unease that I’d be lying in saying that I haven’t felt the effects of as well. It’s a kind of unsettling feeling that, ironically, immersion and building a connection with nature actually seems to calm, even as it also reminds us that we’re on the edge of losing it.

So then, what’s really driving this mass exodus to nature? Is it rooted in fear, a desperate attempt to find clarity in the face of collapse? Or does it stem from a more deep-seated desire to reconnect with something that we’ve forgotten? Maybe it’s both. Maybe we are pulled by two forces at once. The stress and chaos of modern life pushing us out, and the healing, liberating presence of nature drawing us back in.

If nature offers healing and clarity, it’s no surprise that many see it as an escape, an antidote to the discord that modern life has become. But what happens when that escape becomes something more? What happens when nature becomes not just a refuge, but an ideal? A destination not just for a weekend hike, but for the total reinvention of the self?

This is the story at the heart of Jon Krakauer’s, Into the Wild, a book that made me realize that there can be a bleak, sombering, aspect of our desires for a natural connection. The story follows Christopher McCandless, a young man who abandoned his life of privilege to venture across the great North American continent and into the Alaskan wilderness.11 For McCandless, nature wasn’t a temporary break, it was the only place he believed he could live truthfully. He wrote, “I don’t want to know what time it is. I don’t want to know what day it is or where I am. None of that matters.”12 His journey didn’t show that he simply wanted to detach from society but to completely reject it. He gave up his money, burned his IDs, and went out in search of purity, solitude, and some kind of deeper truth.13 His journey was driven by a radical rejection of modern life, but also by a longing for something more authentic than what he had known. This ambition ultimately ended in his untimely death, alone in the Alaskan wilds, right where he said he wanted to be.14 We often think of nature as some holy healer, a frontier that we think would welcome us back if we accept it, but here we find a man, so pushed into desperation and in need of an out, that he neglected the truth that nature needs not to be in tune with us as we do with it, and for that he paid with his life.

McCandless’ quest reminds me of another figure who turned to the wilderness in search of meaning, though under very different circumstances, John Muir. In My First Summer in the Sierra, Muir documents his time wandering the mountains of California, reflecting on the harmony and spirituality he found in the natural world.15 He made assertions such as, “Every hidden cell is throbbing with music and life,” and, “no wonder the hills and groves were God’s first temples.”16 His relationship to nature showed an understanding that to walk among trees and mountains was to be in the presence of something sacred. His writings are filled with wonder and gratitude. He didn’t reject civilization so much as he found something in nature that civilization couldn’t give him: stillness, humility, and a sense of belonging to something far greater than himself. That type of reverence Muir expressed for the natural world is something I don’t think many understand the cruciality of. The natural world doesn’t owe us anything, yet we take from it, destroy it, plunder it, and have the ego to separate ourselves from it. If it were any other kind of relationship, I believe that we would be downright ashamed by our realization that we needed to maintain a connection to it. In contrast to McCandless, Muir felt nature holds a divinity.

Both Muir and McCandless were transformed by their experiences in nature, but in differing ways. Muir saw nature as a teacher, while McCandless saw it as a means of escape from the artificiality of society. One sought understanding, the other sought freedom. Yet, they both turned to the wild for answers, and in many ways, both achieved what they had desired.

Their stories made me think about what I desire from nature, what did my dad desire? Was he looking for an escape? Or was he just looking to pause for a while, take a breath, and understand the world he was put into? Do any of us truly want to get away from our modern lives, or do we just want to rekindle what those before us had in generations past?

But why do we even need to look for an escape? We live in a time where technologies that would have been akin to magic only a few centuries ago are commonplace in the first world. Those who live the busy, work-filled life get to enjoy all the fruits of modern progress. What about the idea of progress suddenly made us shudder? For generations, society has been driven by the idea of progress. More technology, more infrastructure, more convenience. More, more, more, more. So why do we want less? From this I started to question what our idea of “progress” has really done to us. Has it brought us closer to the kind of lives we actually want to live? Or has it pushed us into something louder, more crowded, more alienating?

Jeremy Caradonna, a professor of history at the University of Alberta, challenges the traditional belief that our idea of modernization has been virtuous.17 He argues that while industrialization brought material comfort to some, it also caused a lot of harm for others. Our communities, ecosystems and sense of self have all taken hits as we’ve “modernized.”18 The endless pursuit of growth, he suggests, often comes at the expense of sustainability and connection.19 In questioning the morality of this progress, I think Caradonna is opening up a space to think critically about the world we’ve built. If we’re so advanced, why are so many of us exhausted, anxious and disconnected?

This sense of disillusionment isn’t new. Far from it. Art from nearly a century ago sought to capture this feeling. Reginald Marsh’s 1929 drawing, I tell you, Gus, this town ain’t what it used to be, captured the sense of chaos and decay that urban life brought during a time when industrialization was reshaping American cities.20 The image of two men observing a gritty, overrun New York street shows both a sense of nostalgia for and exhaustion with what life in the city had become. It paints the realization that what was once promised as progress has, in some ways, degraded human experience. Cities that were meant to represent opportunity and modern living had begun to feel like machines that grinded people down. When I look at Marsh’s drawing and read Caradonna’s critique, I start to understand the appeal of nature not just as a place of peace, but as a counterpoint to the world we’ve created. Nature doesn’t move at the speed of profit. It doesn’t buzz, beep or demand constant attention. For many, it offers a vision of life that feels real, or at least, more real than the one defined by highways, cubicles and hours on Tiktok.

A reshaped idea of progress may be a good thing. Who said that it needed to be defined by separation from the natural? Are we not free to determine our own meaning for progress? I had always thought that one of the oddest things about humanity is how we think about freedom. We hear time and time again of stories and instances where people weren’t free to live their lives both in literal terms and more figuratively. But what I always think about is what is keeping them captive? The actions of other humans. The burden of work, of responsibility, of forced responsibility, of living to fit into an idealized version of what you should be, all ideas and constructs created and influenced by others. So if the actions of some parts of humanity are what push down the other, what happens when something else steps into the ring? What happens when everyone is pushed down to similar levels?

I don’t think a more representative example of this exists than the COVID-19 pandemic. For the first time in most of our lives, the world stopped. Everyone was locked indoors, removed from daily commutes and crowded spaces, surrounded instead by the hum of our appliances and the buzz of uncertainty. As weeks turned to months, our own homes, places that in any other case should bring us comfort, now felt claustrophobic. With what was supposed to be our refuge now creating a sense of unease, people again looked for answers in the natural world.

Mitra L. Nikoo, Cerren Richards and Amanda E. Bates discussed in their journal article about how quickly people went back to nature during the pandemic.21 They say that, “people ‘pulsed back’ to nature only one month after returning to shopping for necessities, whereas the return to luxuries lagged far behind.”22 Their article reminded me of the videos I saw of people who had never even camped before suddenly pitching tents, taking hikes, or simply spending time in their backyards. I mean even I vividly remember wanting to get outside. With the wilds of California surrounding me, how couldn’t I? It felt like they were almost calling out to me. My sentiment wasn’t limited to one region though, it was global.23 It was clear to me that people were craving air, craving space, craving freedom. They were looking for something to ease the stress, loneliness and uncertainty that had settled into our lives.

What I found most compelling about this time was the rise of the argument that access to nature should be treated not as a luxury, but as a basic human right and need.24 Same as how most of us stand for food and shelter, people have come to realize that we rely on nature for our emotional and psychological survival. As the pandemic lightened, we didn’t rush back to malls or amusement parks, we rushed back to rivers and trails. I believe that this says something. I believe it says that deep down, we know what we need to feel free.

The pandemic showed that disconnection from nature can be deeply damaging, but also, that reconnection is possible, even in times of crisis. It raised the question, why wait for catastrophe to remember what nourishes us?

In light of the pandemic, I started noticing that for many people within my generation, the desire to reconnect with the natural world isn’t just about a sense of peace or nostalgia. It’s about urgency. It’s about survival. It’s about hope. It’s about trying to find some sense of control in a future that feels increasingly unstable.

I spoke earlier of how Craigan Usher introduced me to the idea of “eco-anxiety,” but following the unease that the pandemic brought on, I wanted to really loop it into how dread can influence us to slip back into nature. Our newfound consciousness about our environment has become more than just a concern, it’s a real psychological weight.25 In exploring the sentiments people of my generation feel about the future I’ve seen that this weight comes in many forms. It’s waking up with dread about rising sea levels. It’s wondering whether bringing children into the world is ethical. It’s feeling powerless in the face of climate collapse while being told it’s our generation’s responsibility to fix it. Usher’s recognition of this responsibility being put onto young people made me feel a sense of being seen. A validation of a sentiment that I have wondered and felt uncertainty about. He treats these feelings seriously, as signs that something is profoundly wrong, both with our environment and the systems we live in.

This is where I have found the connection to nature to be more than superficial. For many young people, returning to nature is not just a retreat, it’s a kind of resistance. It’s a way of saying, “I’m tired of being scared, I want to remember that I am a part of something larger, something older, something alive.”

I find that Usher’s sentiment can also be tied back to Caradonna’s critique of industrial progress. If the previous generations were sold a version of modernity that centered on growth and productivity, many today are choosing to question that path entirely. They’re looking at what that version of progress has done to the Earth, to our communities, to our sense of meaning, and deciding to shift course in a new direction. Reconnecting with nature, then, becomes not just restorative, but transformative. It becomes a way of envisioning a different future, one where we might live more sustainably, more gently, more in tune with the world that holds us.

However, I believe that the question remains. Will this longing translate into real action? Can the desire to reconnect become something more than individual retreats into nature, something systemic, something cultural, something that reshapes how we build, live and relate to our own planet? Therein lies one of the greatest challenges of today. It’s one thing for us to feel the pull back to nature because of our concerns and emotions, but where it ultimately puts us ten, fifty, or even a hundred years down the line is entirely up to what we decide to sustain.

I still think about that evening in the fishing aisle with my dad. Yes, because I needed a jumping off point for this essay, but also because I’m three thousand miles from home, because I am now dropped in the middle of a major city rather than maintaining the comfortable distance that I am used to, because I’m unfamiliar with my surroundings and deeply uncertain for what my own future holds. At the time, it felt so random, just me and my dad looking for a new hobby. But now, after reflecting on everything that moment opened up for me, it feels more like a quiet kind of awakening. Something in him, maybe in both of us, was searching.

As I’ve explored this question, why people today feel the need to return to nature, I’ve come to see that the answer isn’t simple or singular. Sometimes it’s psychological, a need for peace and restoration in a world that never stops moving. Sometimes it’s emotional, a deep desire to feel part of something larger and more meaningful. Sometimes it’s a reaction, a rejection to the noise, pressure and artificiality that seems to define modern life. Sometimes, it’s an act of hope, a belief that maybe, by returning to nature, we can discover a different way of being.

What remains most compelling to me is that the longing for nature is not new, but it feels newly urgent. Whether it’s through awe, anxiety, nostalgia, or necessity, people are realizing that something essential is missing, and they’re looking for it in the rivers, the trees, the quiet trails that lie just outside their hometowns. Maybe they’re not just escaping the world that is our present but just trying to remember it as it was in our past.

I don’t know if there’s a final answer to why we search for answers in nature, but maybe that’s the point. Maybe just asking the question, and following where it leads, is part of what it means to be in search of stillness.

Ballew, Matthew T. and Allen M. Omoto. “Absorption: How Nature Experiences Promote Awe and Other Positive Emotions.” Ecopsychology 10, no. 1 (March 2018): 26-35. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1089/eco.2017.0044.

Caradonna, Jeremy. “Is ‘Progress’ Good for Humanity? Rethinking the narrative of economic development, with sustainability in mind.” The Atlantic. September 9, 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/09/the-industrial-revolution-and-its-discontents/379781/.

Cho, Renée. “Why We Must Reconnect With Nature.” State of the Planet News from the Columbia Climate School. May 26, 2011, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2011/05/26/why-we-must-reconnect-with-nature/.

Krakauer, Jon. Into the Wild. United States: Villard, 1996.

Louv, Richard. “Richard Louv.” Hop Studios. 2016. https://richardlouv.com.

Marsh, Reginald. I tell you, Gus, this town ain’t what it used to be. 1929. drawing: crayon and ink with graphite, 58.5 x 37.3 cm. United States of America. https://www.loc.gov/item/2005694408/.

Muir, John. My First Summer in the Sierra. New York: Houghton Mifflin company, 1911.

Nikoo, Mitra L, Cerren Richards, and Amanda E. Bates. “Rapid worldwide return to nature after lockdown as a motivator for conservation and sustainable action.” Biological Conservation 292, (April 2024): 110-517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110517.

Usher, Craigan. “Eco-Anxiety.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 61, no. 2 (February 2022): 341-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.11.020.

1. Matthew T. Ballew and Allen M. Omoto, “Absorption: How Nature Experiences Promote Awe and Other Positive Emotions,” Ecopsychology 10, no. 1 (March 2018): 1-71, https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2017.0044.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Richard Louv, “Richard Louv,” Hop Studios, 2016, https://richardlouv.com.

5. Renee Cho, “Why We Must Reconnect With Nature,” State of the Planet News from the Columbia Climate School, 2011, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2011/05/26/why-we-must-reconnect-with-nature/.

6. Craigan Usher, “Eco-Anxiety,” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 61., No 2. (2022): 341-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.11.020.

7. Ibid. 342.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Jon Krakauer, Into the Wild (United States: Villard, 1996).

12. Ibid 7. This quote was spoken by Christopher McCandless as written down in his memoir found after he had passed away.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911).

16. Ibid. 196.

17. Jeremy Caradonna, “Is ‘Progress’ Good for Humanity? Rethinking the narrative of economic development, with sustainability in mind,” The Atlantic, September 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/09/the-industrial-revolution-and-its-discontents/379781/.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Reginald Marsh, I tell you, Gus, this town ain’t what it used to be, 1929, crayon and ink with graphite, United States of America, https://www.loc.gov/item/2005694408/.

21. Mitra L. Nikoo, Cerren Richards, and Amanda E. Bates, “Rapid worldwide return to nature after lockdown as a motivator for conservation and sustainable action,” Biological Conservation 292, (2024): 110517, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110517.

22. Ibid. 3.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Craigan Usher, “Eco-Anxiety,” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 61., No 2. (2022): 341-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.11.020.

Between 1350 and 1600, the Renaissance laid the intellectual groundwork for modernity by embracing critical thinking, reason, and creativity. The Renaissance directly threatened the power of the Catholic Church as curiosity led people to contemplate a better world with the wonders of science and the democratic and philosophical teachings from ancient Greece, rather than solely the limited doctrines of the Church. It is also no coincidence that humanism, a deep interest in human potential and development aside from Christian values, came to the forefront of many individuals’ minds as they sought to understand the world for what it was rather than on Christian terms. A newfound inquisitorial drive and human agency paired with the ever-growing corruption of the Catholic Church and its leadership contributed heavily to the Protestant Reformation and creation of new sects of Christianity. Martin Luther, a German monk, played a pivotal role in the Protestant Reformation: first in 1517 with his 95 Theses, and later in 1520 with his Address to the Christian Nobility calling for a new temporal governing power rather than the spiritual power of the Church. This theme of secularism—separation of Church and state—was concurrent with Niccolò Machiavelli’s 1513 book The Prince where Machiavelli explores the difficulties of defining what ‘good’ leadership means, and how effective leadership must operate beyond the restrictions of Christian virtues. Martin Luther and others’ challenges to the authority of the Catholic Church during the Protestant Reformation paired with Machiavelli’s dedication to Renaissance era thinking that shaped his controversial vision for new leadership created a long-lasting debate on the extent of secularism and the use of Christian virtues in government.

While the Catholic Church and the papacy may have started out as a righteous institution bent solely upon God’s will, slowly but surely the corrupt papal leadership tainted the reputation and credibility of the Church. The original practice of finding salvation could be achieved by acts of devotion to God and to faith; to be forgiven would require turning away from the original sin and giving back to one’s spiritual community. When the mission of the Crusades was first encouraged by Pope Urban Ⅱ in 1095, the practice of genuine salvation was diminished to plenary indulgences which granted full remission of sins to those who volunteered to partake in the Crusades. Later, Pope Leo Ⅹ (1513-1521) distanced salvation even further from its original meaning by offering indulgences as monetary transactions, which allowed the papacy to greatly enrich the Church. This was directly contradicting the Gospel of Luke which urges, “Take heed, and beware of a covetousness: for a man’s life consisteth not in the abundance of the things which he possesseth” and the counsel given by the apostle Paul to Timothy asserting “For the love of money is the root of all evil: which while some coveted after, they have erred from the faith.”1 As it was each Popes responsibility to interpret and uphold God’s word, they fell under scrutiny by citizens and other members of the Church who believed them to be misusing their power and supposed divine right to manipulate the Church’s practices to benefit themselves.

Martin Luther, concerned by the moral degeneration of the Church, set the Reformation of the Catholic Church into action in 1517 with his 95 Theses which laid out the illegitimate practice of the Church offering indulgences, which could be paid to repent for sins.2 The practice of indulgences was a power claimed by the Pope, which created a middle person in God’s judgement and his divine right to determine the salvation of his followers; this idea was at the heart of Luther’s 95 Theses as he wanted to raise a debate about the Church’s misguided practices.3

Luther may have been the first to become the face of the Reformation as he successfully spread his writing through the power of the printing press in vernacular languages across Germany and beyond, but others, such as John Calvin, also made a significant impact and gained a following in the footsteps of Luther. John Calvin, a French Pastor, wrote The Necessity of Reforming the Catholic Church in the 1540s. The text is divided into three sections focusing on worship and salvation, the sacraments, and church government. Calvin claimed that the legitimate worship and comprehension of the idea of salvation by the papacy had been rendered “obsolete”, that their use of the sacraments and word of God was extremely “polluted”, and finally that the government of the Church had become a “tyranny.” The form of worship that Calvin suggested was one in the vernacular language that people could truly understand instead of “mutter(ing) over confused prayers in an unknown tongue” (i.e. Latin), as well as experiencing a close connection to God directly, rather than having to be attached to a patron of the Church in order to practice. In terms of the sacraments, Calvin explains how the Church patrons—such as the Pope, Bishops, and Priests—do not uphold the expectation of accurately teaching God’s word, and that the sacraments have been “sullied” by the patrons’ self-serving interpretations of the holy texts. The last piece Calvin touches on is the Church’s government; he asserts that the majority of the leading patrons are lazy and not diligently upholding their responsibility to teach and exemplify God’s word. Calvin’s The Necessity of Reforming the Catholic Church is similar in message to Luther’s 95 Theses, but Calvin specifically aims to explain the current standing and circumstances of the old (Catholic) and new (Protestant) Church to the people in clear language, whereas Luther’s 95 Theses were more of a shortened list of the Catholic Church’s grievances addressed to fellow churchmen.4

Within these two influential pieces of writing, Luther and Calvin convey similar messages, ultimately calling for the reform of the Church and the possibility of a better alternative. While Calvin and Luther align in these prior pieces, they seem to differ in Luther’s Address to the Christian Nobility written in 1520. Luther not only restates his prior challenges against the corrupt Catholic Church practices and misconceptions but also poses a new question about the potentiality of temporal (local) leaders over the spiritual leaders of the Church. Luther claimed that the temporal leaders, such as local princes and other authorities not directly tied to the Church, were baptized just as any other priest or bishop, and should therefore have the same opportunity to lead. To support this idea, Luther challenged the authority of mere priests and bishops as they have been given power or appointed by a higher authority, just as any other could be, and consequently that they were simply officeholders. Ultimately, Luther is introducing the idea that different regions should have the option of local religious authority, rather than that of an ever-growing more distant Church bureaucracy.5

The Address to the Christian Nobility may seem to be a writing in favor of the ‘greater good’ for the people, their religious practices, and governance, but it is also important to consider the impact that Luther’s audience and the amount of pressure he was facing from the Catholic church in the 1520s could have had on the intentions of the text. Around the same time that Luther wrote the Address to the Christian Nobility, Hans Schwarz—a Lutheran theologian and scholar—clarified in “Luther’s Life and Work” that Luther had already been pushed by the Catholic Church and many of its patrons to stop the printing and spread of his writings.6 Luther, naturally, did not comply with the Church’s order and was forced into hiding after being excommunicated by the Church for disregarding their order.7 Luther’s audience, as hinted by the title, was the German Christian nobility. Not only was he trying to persuade them to buy into his sentiment towards the need for Reformation, but Luther also offered a shift in governing power to temporal leaders which would positively impact the nobles themselves. Therefore, Luther was in pursuit of personal security in addition to general support for the Reformation.

Martin Luther’s proposition to replace spiritual leaders with temporal ones can be attributed to the corruption he saw in the Church, but also in the way he believed that the temporal powers held proper institutional powers to govern beyond the Church.8 Luther explicitly said that the “work” of spiritual leaders is to teach and uphold God’s word, whereas temporal leaders “bear sword and rod with which to punish the evil and to protect the good,” meaning that their work was to enforce God’s word by sword and punishment—if need be—a power he did not believe could be held by spiritual patrons of the Church.9

Far off from Martin Luther’s sentiment towards the virtue of religion but close to Luther’s idea of the necessity for temporal powers was Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince. Nicolo Machiavelli’s political career did not begin when he wrote The Prince in 1513 but instead began in the short-lived Republic in Florence that formed during the Italian Renaissance. Eric Voegelin, a German-American political scientist, explains how Machiavelli got his start in Florence after the Medici family—wealthy bankers who gained political power and eventually rose to govern Florence—were ousted by Charles ⅤⅠⅠⅠ of France who led an invasion on Italy in 1494. After the removal of the Medici family, the Florentine hereditary monarchy was replaced with a republic in which Machiavelli served as a diplomat and secretary of foreign affairs.10 Machiavelli only served in the position until 1512, when France had suffered enough defeats trying to secure control of Italy, and the Medicis again rose to power, leading to Machiavelli being dismissed from his position and exiled to his family home outside of the city where he wrote The Prince.11

In The Prince, Machiavelli engaged in complex debates about what it means to be a good leader, reflecting on the different forms of government and leadership he experienced in Italy. Machiavelli neglects writing of the republic and instead explores principalities: a state that is governed by one sole authority—a “prince.”12 Machiavelli categorized principalities into two separate entities: new and old. Old principalities are those in which the prince is chosen by hereditary or traditional power lines, whereas new principalities have a prince who has been chosen by the people or another authority to rule, whether based on patronage (what he calls good fortune) or merit (experience and knowledge). Machiavelli explained each of these principalities as having different strengths and weaknesses, but he laid out many qualities he believes any prince should learn to balance when governing such as liberality and meanness, clemency and cruelty, and faith and religion.13

Machiavelli asserted his position on the roles religion and church values have in politics in Chapter 18 of The Prince, where he revealed when and how a prince should promote or reject religious values while governing the state. In this chapter, Machiavelli anticipates Luther’s belief that spiritual leaders could not carry out the force needed to protect states like temporal leaders could, and further expanded upon it by adding that Christian virtues do not permit a prince to govern in a way that prolongs the survival of the state and its security—in both land and the prince’s rule.14 Graham Maddox, a professor at New England University who studies political thought and comparative politics, argues that Luther and Machiavelli both “set out to deconstruct the political authority of the Church” while urging a separation of church from the state government, but they diverged in the ways they relied on scripture and literature when developing their political philosophies.15 Maddox explained that Luther derived his philosophy from “pristine Christian writings” and “the unmediated working of the (holy) Spirit,” whereas Machiavelli sought to “bypass Christianity altogether” by using ancient classical and Latin texts to develop a philosophy disconnected from the teachings of God.16 Where Luther merely urged a separation of powers between the Church and the State but temporal leaders who still practiced the doctrines of Christianity, Machiavelli challenged the traditional practice to a greater extent—in a way Luther would likely not have agreed with—by arguing that the prince should not stay within the confines of what Christianity permits, but should rely instead on his own agency and judgement.17 Although Machiavelli does not believe Christian virtues have a place in government or politics, he did argue that sometimes it is advantageous for a prince “to appear merciful, faithful, humane, religious” when it can boost his own reputation and popularity.18

John Calvin and Martin Luther would have supported a form of secularism that separated the church and the state, but not one where Christianity and its virtues were absent from governing leaders. Both men became the backbone of the Protestant Reformation, challenging the unrivaled power of the Catholic Church, but not the worth of the Christian Church as a whole. Machiavelli, on the other hand, did not believe mere secularism to be enough, but instead that Christian virtues had reached the end of their dominant role in the government. Calvin and Luther’s lasting devotion to Christianity and the Church made them key players in the Reformation, but not direct embodiments of Renaissance era thinking which would have relied on science and classical texts from ancient Greece and Rome, like Machiavelli’s philosophy more closely did. This divide in Reformation and Renaissance thinking did not end in the early-mid 1500s at the times they wrote their most influential pieces, but it continued throughout the late 1500s and 1600s as religious wars over Catholicism and Protestantism combined with struggles over control for political and social power engulfed all of developing Europe. The forms of secularism that Calvin and Luther inspired did not instantly become reality, and Machiavelli’s idealized separation from Christian values in government would take even longer to come to fruition than the separation of powers the Reformers sought. These early 1500s thinkers forever challenged the status quo, and later scholars in the Age of Enlightenment (17th and 18th centuries) and the progress towards the American (1775-1783) and French (1789-1794) Revolutions may not have materialized the same without their fundamental contributions.

1. The New Testament (Intellectual Reserve, Inc., 2014), 1299, 1511, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/bc/content/shared/content/english/pdf/language-materials/83291_eng.pdf.

2. Martin Luther, 95 Theses (1517), http://reverendluther.org/pdfs/The_Ninety-Five_Theses.pdf.

3. Luther, 95 Theses.

4. John Calvin, “The Necessity of Reforming the Catholic Church,” in Ideas and Identity in Western Thought: Readings in Politics, Economics, Society, Law, and War, ed. Micheal Holm (Cognella, Inc., 2023), 76.-80.

5. Martin Luther, “Address to the Christian Nobility,” in Ideas and Identity in Western Thought: Readings in Politics, Economics, Society, Law, and War, ed. Micheal Holm (Cognella, Inc., 2023), 70.

6. Hans Schwarz, “1: Luther’s Life and Work,” in True Faith in the True God: An Introduction to Luther’s Life and Thought (Augsburg Fortress Press, 2015), 24-25, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13wwwc2.5.

7. Schwarz, “1: Luther’s Life and Work,” 25.

8. Luther, “Address to Christian Nobility,” 70.

9. Luther, “Address to Christian Nobility,” 70.

10. Eric Voegelin, “Machiavelli’s Prince: Background and Formation,” The Review of Politics 13, no. 2 (1951): 143, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1404762.

11. Voegelin, “Machiavelli’s Prince: Background and Formation,” 143.

12. Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. Rufus Goodwin (Dante University Press, 2003), https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Prince/bRdLCgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover.

13. Machiavelli, The Prince, 74-86.

14. Machiavelli, The Prince, 83-86.

15. Graham Maddox, “The Secular Reformation and the Influence of Machiavelli,” The Journal of Religion 82, no. 4 (2015): 539-540, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1206519.

16. Maddox, “The Secular Reformation and the Influence of Machiavelli,” 539.

17. Machiavelli, The Prince, 84.

18. Machiavelli, The Prince, 85.

Every school year, without fail, there was always one moment that I dreaded: the first week icebreaker. “Get in a circle, let’s go around and introduce ourselves. Say your name, favorite hobby, and where you are from!” Although it seemed harmless enough, the question, “Where are you from?” carried more weight than peers around me probably realized. During the first couple years in America, I answered without hesitation. “I’m from Korea,” I’d say proudly. But a few years later, the question began to feel trickier than it should be. By the time I was in high school, I started wondering if I was supposed to say “California,” as we had been living there for a while by then. On a daily basis, I spoke more English than Korean. I got more used to American culture than Korean culture. And more importantly, I did not want to be seen as too foreign. So when it came time to introduce myself again, I hesitated for a moment. “Well, I was born in Korea, but I live in California.” That moment of hesitation marked the beginning of a deeper personal split. It seems like such a small moment, but it stayed with me. It was the first time I realized that identity was not what I could state so confidently, but something I had to choose, and every choice came with its consequences. Saying “Korea” felt like risking being labeled as an outsider, but “California” felt like denying a part of myself. The small moment of introducing myself every school year became a larger conflict. One that still follows me into college, and even casual conversations with strangers.

For many immigrants, identity is a constant negotiation. Torn between two worlds, we are often told to assimilate with one culture, while constantly being reminded of our foreignness. We carry our family’s language, culture, and traditions, while attempting to adapt to the norms and expectations of the new society. This “in between” state creates the sense of internal conflict, as well as alienation. “Too foreign for home, yet too foreign for here” becomes more than a saying, but a lived reality with no clear sense of feeling fully home in either place. In the end, we are simply left to ask ourselves: Who am I? What am I? Where do I belong? And at the heart of it all is the question that shaped my childhood: Can immigrants ever truly feel at home in one culture?

I started noticing the ways this question extended beyond just me, when I compared myself to my younger brother. Unlike me, he was too young to remember living in Korea. He is also much more fluent in English than in Korean, and more “Americanized,” as my parents would say. I recently asked him whether he thinks of himself as more American or Korean, in which he paused for a moment before answering. “American, I think. I don’t really speak Korean well, and sometimes I feel out of place when we go to Korea. I can’t even understand everything they’re saying.” His experience reflects an important truth, that even within the same household, immigrant experience can differ dramatically. This generational and linguistic gap parallels findings by Rubén G. Rumbaut, who explains how immigrants experience “segmented assimilation,” in which identity and belonging split along the lines of class, language, and culture. While some preserve strong ties to their home country, others lean more towards their host country, often depending on how accepted or marginalized they feel in the society. Although my brother’s answer was not surprising, it still stuck with me. While I am constantly negotiating between two identities, he feels a clearer sense of belonging, because American life is what he has always known.

Scholars have long studied how immigrants come to develop their identities. Nancy Foner, et al note that identities are “amenable to change” through dynamic processes shaped by experience and social interaction. Immigrants don’t simply assimilate or resist assimilation, but rather navigate through multiple identities that shift over time. This explains why I once clung to my Korean roots and now find myself feeling in between identities depending on the settings—school, home, or public spaces. Déborah B. Maehler and Jessica Daikeler’s extensive research on first generation immigrants further reveals how cultural identity can often include both host and home cultures in complicated ways. For many, identity becomes something hybrid rather than singular. This hybridity may allow room for flexibility, but it also creates discomfort as they may belong partially to two places, but not fully to either. This duality is especially clear in the way I switch between languages and behaviors depending on who I am with. At home, I instinctively call my parents “eomma” and “appa.” But at school or another environment, I refer to them as my mom and dad, in the “American way.” I live in this kind of cultural code-switching, trying to pass seamlessly between two different worlds.

This dilemma becomes even more complicated when it comes to national identity. Jennifer Wenshya Lee and Yvonne M. Hébert explored how youth of immigrant and non-immigrant origins in Canada acknowledged their sense of belonging. They found that youths of immigrant origin expressed a more complex relationship to the idea of “being Canadian” than of their non-immigrant peers. When two groups were asked to define what “being Canadian” means to them, findings show that immigrant origin youths described Canadian identity with more rational statements, such as “peaceful country” and “high standard of living,” while non-immigrant youths who presented their identity with more passion and confidence, like “proud” and “highest standard of living.” This difference shows a discrepancy in how rooted each group feels in the national culture. Immigrants often define identity based on ideals because they don’t feel reflected in the dominant cultural narratives like the national holidays and symbols, things one can belong to without necessarily “looking the part.” As a result, “being Canadian” becomes more about the principles than shared traditions. I’ve often found myself navigating that same sense of disconnect, trying to present as fully American yet still feeling out of place. Through language, clothing, even humor, I try to fit in. But there’s always something: a stranger asking where I’m really from, or complimenting my English. These aren’t blatant aggressions, but small reminders that my belonging comes with conditions. When national identity is closely knitted to cultural symbols and traditions that exclude their experiences, immigrants can feel like outsiders. And so they cling to values they can align with, like freedom and democracy, while still detached from the cultural references that non-immigrants take for granted. Many immigrants learn what national identity is supposed to mean, but still question whether that identity truly includes them.

But maybe the goal isn’t to fully belong in one culture. In their analysis of immigrant identity in the contexts of the U.S. and Sweden, Ylva Svensson and Moin Syed found that U.S. participants were more likely to define themselves using multi-ethnic categories like “Asian-American,” rather than the national labels alone. While the participants often described themselves as feeling different from the mainstream culture, they also felt a strong sense of belonging through communities that embraced these differences. In contrast, the Swedish participants struggled more with finding community around the deviations from the norm. This suggests that immigrant identity, particularly in the U.S., is best understood as a negotiation between the individual and society. Instead of resolving cultural contradictions, many found ways to live within them, redirecting differences as a source of connection among those who reflect their experiences. As Svensson and Syed argue, identity formation is about finding coherence amidst contradiction. That idea started to feel real during the first few months of college. I started noticing how almost everyone around me carried their own version of a layered identity, whether it was a name that didn’t come easily to others, a mix of languages spoken at home, or the experience of growing up between two cultures. This wasn’t just for immigrants; even those who had grown up in America often had stories shaped by regional differences or cultural traditions that didn’t always align with the conventional culture. No one apologized for it. No one felt the need to explain. And slowly, I stopped explaining myself too. The things I used to second-guess, like the way I’d count in Korean, switch between languages in my head, or wonder whether I was too Korean or not Korean enough, eventually started to feel like facts, not contradictions. Being different didn’t feel like something to fix anymore, it just felt normal. In a strange way, the question that haunted me growing up–where are you from?–has further pushed me to think more about who I am. Rather than choosing between two countries, maybe I can claim both, because my identity is not split, but layered.

For many of us, home is something we build piece by piece, not what we inherit fully formed. It doesn’t simply exist in one language, tradition, or passport, but in the ongoing process of choosing and blending. Through this, I’ve started to realize that identity doesn’t have to be either resolved or clearly defined to be real. In fact, maybe the more honest question here isn’t about which culture we belong to, but whether we can belong without needing to be fully understood by either. Can we embrace the complexity of who we are, even when the world around us asks for simplicity? Immigrant identity is not something to be solved, but something to be lived, both imperfect and layered. And within that space, we don’t just learn to exist, but to belong on our own terms.

Foner, Nancy, et al. “Introduction: Immigration and Changing Identities.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, vol. 4, no. 5, Dec. 2018, p. 1, https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2018.4.5.01. Accessed 4 Apr. 2025.

Lee, Jennifer Wenshya, and Yvonne M. Hébert. “The Meaning of Being Canadian: A Comparison between Youth of Immigrant and Non-Immigrant Origins.” Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne de L’éducation, vol. 29, no. 2, 1 Jan. 2006, p. 497, https://doi.org/10.2307/20054174. Accessed 4 Apr. 2025.

Maehler, Débora B, and Jessica Daikeler. “The Cultural Identity of First-Generation Adult Immigrants: A Meta-Analysis.” Self and Identity, vol. 23, no. 5-6, 8 Sept. 2024, pp. 1–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2024.2399559. Accessed 4 Apr. 2025.

Rumbaut, Ruben G. “The Crucible Within: Ethnic Identity, Self-Esteem, and Segmented Assimilation among Children of Immigrants.” International Migration Review, vol. 28, no. 4, 1994, p. 748, www.jstor.org/stable/2547157, https://doi.org/10.2307/2547157. Accessed 4 Apr. 2025.

Svensson, Ylva, and Moin Syed. “Linking Self and Society: Identity and the Immigrant Experience in Two Macro-Contexts.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, vol. 64, 19 Aug. 2019, p. 101056, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101056. Accessed 4 Apr. 2025.

Virginia Woolf, in her essay “Street Haunting: A London Adventure,” invites us into the mind of the flâneur, an individual who sheds their specific identity to become an anonymous observer, merging with the city’s vibrant ebb and flow. The goal is not arrival, but the journey itself; the purpose is observation, absorbing the surfaces of the city like “the glossy brilliance of the motor omnibuses; the carnal splendor of the butchers’ shops … the blue and red bunches of flowers burning so bravely through the plate glass of the florists’ windows” and the human dramas playing out within that urban theatre (Woolf 2). But what does this act of “street haunting,” this purposeful aimlessness, mean in the 21st century, in a city like Boston, and for someone like me—a Korean student navigating a landscape both foreign and strangely familiar? Woolf’s flaneur sought anonymity. Yet, wandering through the Koreatown neighborhood in Allston, I find my identity not shed, but perhaps refracted, illuminated in unexpected ways by the street I haunt. This essay seeks to explore my own process of street haunting in Allston, questioning how the unique, almost retro atmosphere of this specific place interacts with Woolf’s ideas and what this exploration reveals about identity, time, and the experience of diaspora in a modern American city. Why does this particular corner of Boston seem suspended in a different era, and what does observing it teach me about belonging, memory, and the act of seeing?

My journey into this exploration began not with Woolf, but with groceries. As a Boston University student living relatively close by, Allston’s Koreatown became a practical destination for familiar foods and tastes of home. Yet, beyond the aisles of tteokbokki kits and Shin Ramyun, something else caught my attention. It wasn’t just Korean; it felt like vintage Korean. Walking down Harvard Avenue or Brighton Avenue, I was caught by shop signs flaunting Hangul (Korean alphabet) fonts popular in the 1980s or early 1990s—slightly clunky, bold, sometimes with drop shadows with evident pre-digital design. Restaurants featured distinct retro decorations—colors of wood paneling, perhaps, or specific floral patterns on seating—that felt reminiscent of dramas my parents used to watch. It contrasted sharply with modern day Seoul, where minimalist, hyper-modern aesthetics prevail.