Since the beginning of 2020, reports on the novel Coronavirus (COVID) have monopolized international media, politics, and even private conversations. Such reports serve to track the geographic spread of not only infection, but also fear. The origination of the disease in China renders the country a focal point for criticism and reflection on the state’s response to the disease; while the extreme measures taken to negate the spread of the virus have served to substantially reduce China’s rate of infection, domestic and foreign voices alike condemn the governmental response to the disease as altogether inadequate.1 The time elapsed between the discovery of the virus and the measures taken to contain it have since caused global repercussions in health, economics, and politics. The falsehoods leading to this delay, along with the resulting crises, stem not only from the deliberate promulgation of misinformation by the Chinese government, but also from a complex bureaucratic web entangling the interests of the Chinese medical community and local government with those of the central government. This subversion of truth explicitly and implicitly served to downplay the danger of COVID, and simultaneously overemphasized the effectiveness of the Chinese response to the virus. Owing to a system prizing bureaucratic loyalties over truth, the Chinese state allowed for the

Global panic around COVID has not only distressed the world of healthcare, but has shifted the very construct of routine, casting the international community into a state of chaos. Administrative precautions have impacted everything from sports games to elections, affecting every paradigm of daily life. States have instituted partial and total lockdowns to slow the spread of the virus, closing businesses, schools, and even borders. The resulting economic alarm has caused a drop of nearly 10,000 points in the Dow,2 in turn bringing about speculation of a recession.3 The preventative measures taken against COVID, along with the subsequent economic and social backlash, prove all-encompassing, fed by international fear of the unknown around both the disease and its consequences.

These measures and their ramifications accentuate timeliness as the primary determinant of prevention Initial inaction exaggerated the severity of the virus. On December 31, the Chinese government initially informed the World Health Organization of the appearance of an “unexplained viral pneumonia” with “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.”4 However, a study published by doctors in the Wuhan Jinyintan hospital reports the first case of COVID as December 8, elaborating that, by the date of China’s official statement, significant numbers of infected individuals held no contact with the virus’ point of provenience.5 An investigation by the University of Southampton explains how this delay functioned to augment the scale of the virus, studying how, if the coronavirus had been discovered in China “one week, two weeks, or three weeks earlier, cases could have been reduced by 66 percent, 86 percent and 95 percent respectively.”6 This study proves that the lack of efficiency with which the Chinese government confirmed and contained COVID cases relates directly to the spread of the disease. Although China’s governmental enforcement and civic compliance worked to contain the disease, COVID’s ever-increasing death toll highlights the government’s concealment of critical data, from both the Chinese and international public.

The delay of the governmental response could have arisen partially from the nature of COVID. Originating in Wuhan, China, COVID presents as symptomatically flu-like, and only causes severe health repercussions like pneumonia or organ failure in a fraction of cases.7 These illusions of the virus caused initial misdiagnoses among healthcare providers and insufficient measures among infected individuals to prevent further circulation.8 Along with the virus’ presumed ability to transmit before the appearance of symptoms,9 these factors render the disease conducive to rapid and undetected transmission.

However, the furtive character of COVID does not serve to completely explain the temporal gap between the initial outbreak of the virus and Chinese government’s measures to contain it. On December 26th, the discovery of a coronavirus with “87 percent similarity to SARS,”10 began to circulate within the Wuhan medical community. Although the association with SARS, which had a 10% death rate,11 should have sounded immediate bells of alarm, the Wuhan Health Commission waited five days to release a report. Within the report, the government highlighted the “ongoing investigation for the pathogen,” along with the lack of evidence for human-to-human transmission.12 These findings negated those of Wuhan doctors Liu Weihang or Ai Fen, who had diagnosed a patient with an “unknown coronavirus” as early as December 16.13 Fen had also called the WHC’s attention to infections unrelated to the Huanan seafood market, the recognized initial point of infection.14 However, Chinese authorities continued to deny this proof of human-to-human transmission until January 20th.15 By its direct contradiction of medical advice, the government concealed the full risk of the virus, thereby risk allowing uncontrolled spread for over a month.

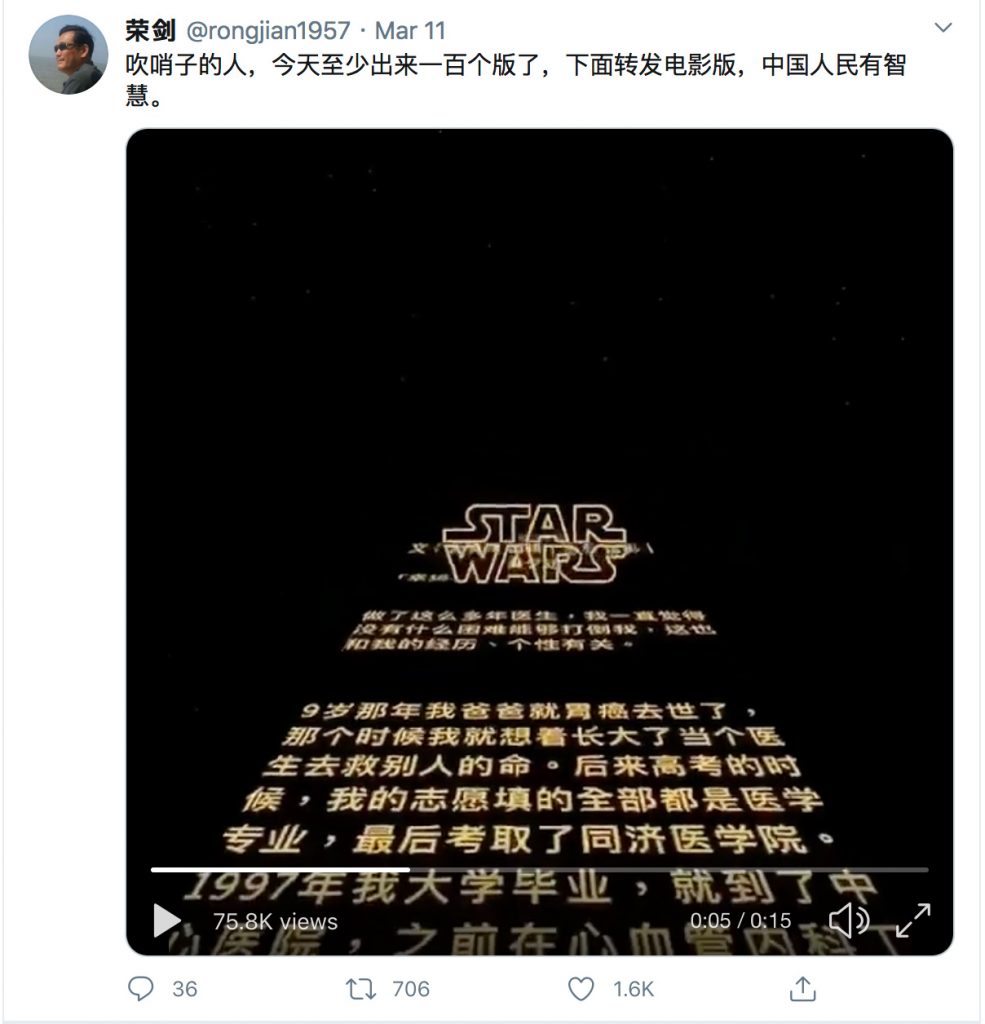

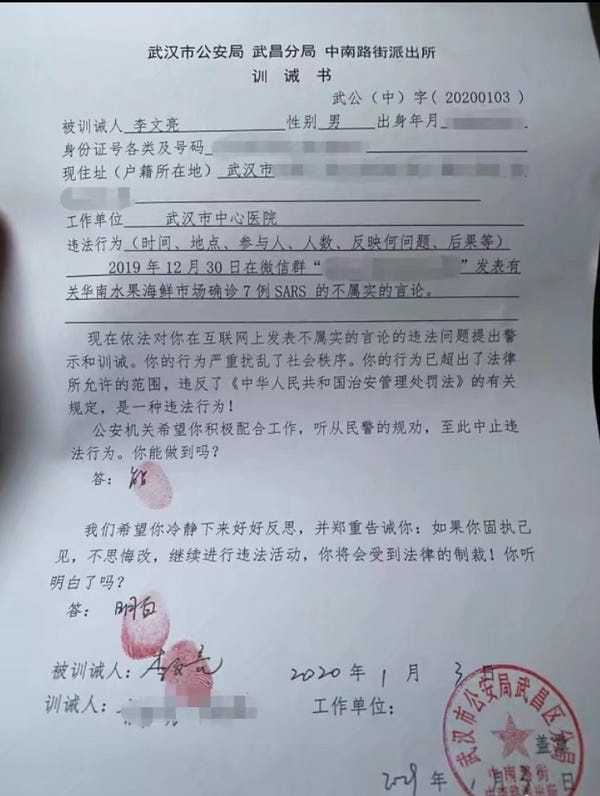

Moreover, the government’s failure to control the virus did not result from the simple neglect of medical opinion, but rather demonstrated active efforts to obfuscate information on the part of bureaucratic officials. Fen, after her initial warning to the WHC, posted a photo of the SARS diagnosis on WeChat in an attempt to inform and protect the community.16 Shortly thereafter, the government removed this message and any reposts, causing citizens to share it in code, or even integrate it into the Star Wars theme (Fig. 1).17 Fen also described a directive given to medical workers, in which the WHC stated that “public disclosure related to the illness was forbidden,” thereby silencing her both online and in person. Dr. Liu Weihang made a similar attempt to notify the public, and as a result was detained and ordered by the local government to sign a document ordering that he desist from “making false comments”18) (Fig. 2). A week after his mandated court appearance, Dr. Li Weihang contracted COVID, leading to his eventual death. Dr. Weihang’s martyrdom, along with the WHC’s censorship of Fen, show how the local government worked to downplay the virus through the conscious effort to block medical efforts to warn the public, in turn intensifying the infections and casualties.

This silencing of the medical community by the WHC reflects the greater theme of local retainment of medical information, both from the central government and from the public. Chinese national news reports that Gao Fu, the Chinese CDC director general, discovered the epidemic in Wuhan on December 30th,18 nearly a month and a half later than Chinese data currently backdates the first case of coronavirus.19 The release described Fu’s discovery of two indications of a pneumonia-like epidemic during a routine scan of the Wuhan Health Commission’s group-chats. The report states that these cases “were not entered into the direct reporting system according to the law, but were reported step by step,”20 thereby attributing the gap in communication between the WHC and CDC to a simple misstep. However, through its overt attempts to censor medical opinion, the WHC proves this communicative inconsistency to have been more than a simple mistake.

Although the Chinese national news portrayed this suppression of medical fact to the CDC as an irregularity, the problem of misinformation between tiers of government has proven a historic issue within China. Katherine Mason, a researcher at Brown University, describes the nature of the “step by step” communication which Gao Fu cites as the reason for the CDC’s delay in action. In a study of post-SARS health reforms, Mason discusses how officials “protected certain knowledge that local officials saw as belonging only to them and their local collaborators,”21 thereby explaining why the WHC kept the initial information about the coronavirus to itself. The local government, she explains, tends to uphold a view of guanxi, or personal relationships, in their communication of data. This data, therefore, has filtered “step by step” through personal relationships into the hands of the national government. Although China introduced a centralized reporting system after the SARS outbreak of 2003,22 Gao Fu’s statement shows that this relationship-based communication of data has continued to cause delay and misrepresentation of fact, thereby leading to the downplay of the risk of COVID.

This misrepresentation has extended not only between the local and national governments, but has even infected the local medical community, as exemplified by the disparity between local and national data. The WHC’s first statement about the epidemic stated that “twenty-seven cases have been found, of which 7 are in serious condition.”23 This statement contradicts a later release by the Chinese CDC, which shows that medics had already confirmed 104 infections in December, including 15 deaths.24 This inconsistency owes a great deal to what Mason calls “technological hypertransparency:” a phenomenon in which epidemiologists, employed by the government, define what data proves “correct” regardless of truth, and therefore pressure local medics to revise any data outside of the realm of “correctness.”25 In turn, this system creates a closed-circuit route for information, filtering out any data which would seem inopportune to the Chinese government. The perpetuation of falsehoods has thus created a dearth of information which renders the Chinese government helpless against threats to national health. Therefore, the inaction of the Chinese government owes, at least in part, to the WHC’s systematic suppression of truth.

The skewed numbers of cases in Wuhan caused a lack of government alarm, therefore increasing the scale of the virus. On January 19th, although the CDC had identified the existence of the “new coronavirus” almost two weeks earlier,26 thousands of people gathered in Hubei province to celebrate the Lunar new year. An interview with an anonymous citizen revealed how holiday travel “spread the coronavirus through travel and large public gathering[s]… as many people return[ed] to family homes for the festival.” The lack of precaution taken on the part of local and national officials, despite the medical knowledge of human-to-human transmission of the disease, caused a significant spread of infection,

While many sought to place blame for the infections resulting from this gathering,27 the responsibility rested upon the central government as much as the local. The current mayor of Wuhan, Zhao Xianwang, responded to pressures for his resignation, stating that “his hands were tied by rules that required Beijing’s approval before releasing sensitive information.”28 Xianwang, in this mitigation of blame, references the control over information held by central Chinese authorities, showing, much as Guo Fu did, that government inaction resulted primarily from gaps in the chain of command. However, where Fu illustrated the gaps as due to local authority, Xianwang shows that the lack of precaution resulted from the silencing of the local government by the national.

In reality, the local and central governments take equal roles in this propagation of misinformation and the resulting lack of precaution. Xueguang Zhou, a professor and senior fellow at Stanford, attributes this to the “inspection and appraisal” practice in China, by which he explains the central government’s creation of “elaborate internal promotion ladders and reward and penalty systems to incentivize bureaucrats.”29 This method exposes the central government’s manner of controlling smaller branches, such as the ministry of health or the local government, through a system of promotion and punishment. The corruptive nature of this “inspection and appraisal” serves to illuminate Xianwang’s delay in informing the public about the novel coronavirus, explaining how the sacrifice of morality proves necessary for political advancement. This convoluted bureaucracy proves that the blame for misinformation and the subsequent precautionary inaction rests not with the local government alone, but rather points to a greater issue within the structure of Chinese bureaucracy.

The responsibility of the central government in this chain of inconsistency rests in its acceptance and propagation of misinformation, owing to an overarching devaluation of truth for political expedience. Mason explains the central government’s acceptance of visibly faulty data through the definition of “public secrets” or information “that people knew was fake, but acted like it was real.”30 She shows that both the general public and the inner circle (“neibu”) of the Health agency participate in this acceptance of falsified information,31 however, while the general public has no choice but to accept the information provided, the neibu consciously disregards fact in favor of fabrication. This acceptance of lies which benefit a subjective common goal, although momentarily advantageous to economic or political strategy, proves ultimately detrimental, as shown by the extenuating distress caused by COVID.

While the falsehoods originated in this complex authoritarian structure, the national government continued to produce this misinformation on a far greater scale than the local. On February 6th, the Chinese national government awarded Wuhan doctors Zhang Dingyu and Zhang Jixian with “great merit” for raising alarm about a new coronavirus.32 The praise of the doctors’ “decision-making and deployment of the Party Central Committee” served to glorify the very system which caused a significant delay in informing the public of COVID, and therefore failed to protect its citizens. Furthermore, the recognition of Jixian’s December 27th report of pneumonia clusters as the “first notice” of alarm proves a disregard for earlier cases, and therefore a propagation of misinformation. The harsh contrast between the accolade of these doctors and the silencing of Ai Fen and Liu Weihang illustrates the central government’s prioritization of image over safety and the resulting lack of caution.

The broadcasting of national successes to overshadow legislative deficiencies serves to enhance the catastrophe caused by that deficiency by further obfuscating the truth. Katherine Morris defines this tactic of the central government as “Performative Hypertransparency,” explaining how the government uses prominent symbols, such as the banners around China (Fig. 3) or the 10-day hospital in Wuhan, to glorify the state’s medical system.33 However, through the faulty appearance of control, this tactic only contributes to China’s shortcomings in virus control, shielding these faults rather than targeting them.

The national emphasis on the government’s successful management of the COVID outbreak serves to quell the damage done to Chinese public image; however, this propaganda only amplifies the systematic concealment of truth which first damaged this image. The purposeful undermining of fact proves a central means of consolidation of control, both by the local and national governments. Yet what purpose does this authoritarian control serve if not to protect those citizens whom it claims to benefit? The outbreak of the novel coronavirus calls into question the limitation of free speech as a safety measure by the Chinese government, proving the risks of governmental censorship not only to the Chinese population, but also to the international community. This realization of inefficiency of the protective abilities by the government, owing to an insuperable constraint on truth, therefore reveals the inadequacy of the entire Chinese system.

Figure 1: A tweet circulating Ai Fen’s warning, modified as the Star Wars theme.

(荣剑. “吹哨子的人,今天至少出来一百个版了,下面转发电影版,中国人民有智慧。 pic.twitter.com/VgCt95sxdK.” Twitter. Twitter, March 11, 2020. https://twitter.com/rongjian1957/status/1237743031316447238?)ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.buzzfeednews.com%2Farticle%2Fryanhatesthis%2Fcoronavirus-covid-chinese-wechat-censored-post-emojis.

Figure 2: The statement Dr. Li was forced to sign, swearing he would not “spread false rumors.”

(Aylin Woodward, “Whistleblower Doctor Li Wenliang, Who Was Censored after Sounding the Alarm about the Coronavirus, Has Died in Wuhan,” Business Insider (Business Insider, February 6, 2020), https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-whistleblower-doctor-li-wenliang-in-critical-condition-2020-2.condition-2020-2

(Aylin Woodward, “Whistleblower Doctor Li Wenliang, Who Was Censored after Sounding the Alarm about the Coronavirus, Has Died in Wuhan,” Business Insider (Business Insider, February 6, 2020), https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-whistleblower-doctor-li-wenliang-in-critical-condition-2020-2.condition-2020-2

Figure 3: Banners around China enforce public safety precautions. “Even during spring festival, staying home is a good idea”

(Yuhan Xu and Elena Renken, “China’s Red Banners Take On Coronavirus. Even Mahjong Gets A Mention,” NPR (NPR, March 1, 2020), https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/03/01/805760905/chinas-red-banners-take-on-coronavirus-even-mahjong-gets-a-mention.)

(Yuhan Xu and Elena Renken, “China’s Red Banners Take On Coronavirus. Even Mahjong Gets A Mention,” NPR (NPR, March 1, 2020), https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/03/01/805760905/chinas-red-banners-take-on-coronavirus-even-mahjong-gets-a-mention.)

Al Jazeera. “Timeline: How the New Coronavirus Spread.” China News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera, March 19, 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/01/timeline-china-coronavirus-spread-200126061554884.html.

Chen, Nanshan, Min Zhou, and Xuan Dong. “Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of 99 Cases of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a Descriptive Study.” The

Lancet 395, no. 10223 (February 15, 2020). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7.

Chin, Josh. “Wuhan Mayor Says Beijing Rules Partially Responsible for Lack of Transparency.” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, January 28, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-premier-tours-virus-epicenter-as-anger-bubbles-at-crisis-response-11580109098.

“Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).” Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, March 19, 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/symptoms-causes/syc-20479963.

“Dow Jones Industrial Average.” MarketWatch. Accessed March 21, 2020. https://www.marketwatch.com/investing/index/djia.

Huang, Kristin. “Wuhan Doctor Says Officials Muzzled Her for Sharing Coronavirus Report.” South China Morning Post, March 11, 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3074622/coronavirus-wuhan-doctor-says-officials-muzzled-her-sharing.

Lai, Shengjie. “Early and Combined Interventions Crucial in Tackling Covid-19 Spread in China.” Early And Combined Interventions Crucial In Tackling Covid-19 Spread In China | University of Southampton. University of Southampton, March 11, 2020. https://www.southampton.ac.uk/news/2020/03/covid-19-china.page.

Ma, Josephine. “China’s First Confirmed Covid-19 Case Traced Back to November 17.” South China Morning Post, March 13, 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3074991/coronavirus-chinas-first-confirmed-covid-19-case-traced-back.

Mason, Katherine A. The Correct Secret. Vol. 75. Nijmegen: Stichting Focaal, 2016.

Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. “The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) – China, 2020.”

China CDC Weekly. China CDC Weekly, February 1, 2020. http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51.

Rauhala, Emily, and Gerry Shih. “Early Missteps and State Secrecy in China Probably Allowed the Coronavirus to Spread Farther and Faster.” The Washington Post. WP Company, February 1, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/02/01/early-missteps-state-secrecy-china-likely-allowed-coronavirus-spread-farther-faster/.

Rettner, Rachael. “COVID-19 Spread Is Fueled by ‘Stealth Transmission’.” LiveScience. Purch, March 17, 2020. https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-undiagnosed-spread.html.

Schiller, Bill, Nirupama Johri, Helen Branswell Branswell, Andrew Joseph, Pete Leone, and Katherine Janet. “The Coronavirus Questions That Scientists Are Racing to Answer.” STAT, January 28, 2020. https://www.statnews.com/2020/01/28/the-coronavirus-questions-that-scientists-are-racing-to-answer/.

“UCLA Anderson Forecast.” UCLA Anderson, March 16, 2020. https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/centers/ucla-anderson-forecast/2020-recession.

Wei, Lingling, and Chao Deng. “China’s Coronavirus Response Is Questioned: ‘Everyone Was Blindly Optimistic’.” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, January 24, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-contends-with-questions-over-response-to-viral-outbreak-11579825832.

Woodward, Aylin. “Whistleblower Doctor Li Wenliang, Who Was Censored after Sounding the Alarm about the Coronavirus, Has Died in Wuhan.” Business Insider. Business Insider, February 6, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-whistleblower-doctor-li-wenliang-in-critical-condition-2020-2.

Zheng, Sarah. “Wuhan Mayor under Pressure to Resign over Response to Virus Outbreak.” South China Morning Post, February 17, 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3047230/wuhan-mayor-under-pressure-resign-over-response-coronavirus.

“武汉市卫健委关于当前我市肺炎疫情的情况通报.” 武汉市卫生健康委员会. Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, December 31, 2020. http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989.

“武汉市卫生健康委员会关于不明原因的病毒性肺炎情况通报.” 武汉市卫生健康委员会. Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, January 5, 2020. http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2020010509020.

“疫情上报‘第一人‘张继先被给予记大功奖励.” 新京报网, February 6, 2020. http://www.bjnews.com.cn/feature/2020/02/06/685481.html.

荣剑. “吹哨子的人,今天至少出来一百个版了,下面转发电影版,中国人民有智慧。 Pic.twitter.com/VgCt95sxdK.” Twitter. Twitter, March 11, 2020. https://twitter.com/rongjian1957/status/1237743031316447238?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.buzzfeednews.com%2Farticle%2Fryanhatesthis%2Fcoronavirus-covid-chinese-wechat-censored-post-emojis.

“高福的功过祸福:虽万千人吾往矣!.” 口腔溃疡如何根治_发病原因,快速治疗方法,吃什么药,水果_口腔溃疡网, February 18, 2020. http://www.kqm8.com/renwu/1914.html.

1. Lingling Wei and Chao Deng, “China’s Coronavirus Response Is Questioned: ‘Everyone Was Blindly Optimistic’,” The Wall Street Journal (Dow Jones & Company, January 24, 2020), https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-contends-with-questions-over-response-to-viral-outbreak-11579825832.

2. “Dow Jones Industrial Average,” MarketWatch, accessed March 21, 2020, https://www.marketwatch.com/investing/index/djia.

3. “UCLA Anderson Forecast,” UCLA Anderson, March 16, 2020, https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/centers/ucla-anderson-forecast/2020-recession.

4. “武汉市卫生健康委员会关于不明原因的病毒性肺炎情况通报,” 武汉市卫生健康委员会 (Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, January 5, 2020), http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2020010509020.

5. Nanshan Chen, Min Zhou, and Xuan Dong, Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of 99 Cases of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a Descriptive Study, The Lancet 395, no. 10223 (February 15, 2020), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7.

6. Shengjie Lai, Early and Combined Interventions Crucial in Tackling Covid-19 Spread in China, Early And Combined Interventions Crucial In Tackling Covid-19 Spread In China | University of Southampton (University of Southampton, March 11, 2020), https://www.southampton.ac.uk/news/2020/03/covid-19-china.page.

7. “Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19),” Mayo Clinic (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, March 19, 2020), https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/symptoms-causes/syc-20479963.

8. Rachael Rettner, “COVID-19 Spread Is Fueled by ‘Stealth Transmission’,” LiveScience (Purch, March 17, 2020), https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-undiagnosed-spread.html.

9. Bill Schiller et al., “The Coronavirus Questions That Scientists Are Racing to Answer,” STAT, January 28, 2020, https://www.statnews.com/2020/01/28/the-coronavirus-questions-that-scientists-are-racing-to-answer/.

10. Emily Rauhala and Gerry Shih, “Early Missteps and State Secrecy in China Probably Allowed the Coronavirus to Spread Farther and Faster,” The Washington Post (WP Company, February 1, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/02/01/early-missteps-state-secrecy-china-likely-allowed-coronavirus-spread-farther-faster/.

11. Kristin Huang, “Wuhan Doctor Says Officials Muzzled Her for Sharing Coronavirus Report,” South China Morning Post, March 11, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3074622/coronavirus-wuhan-doctor-says-officials-muzzled-her-sharing.

12. “武汉市卫健委关于当前我市肺炎疫情的情况通报,” 武汉市卫生健康委员会 (Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, December 31, 2020), http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989.

13.Josephine Ma, “China’s First Confirmed Covid-19 Case Traced Back to November 17,” South China Morning Post, March 13, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3074991/coronavirus-chinas-first-confirmed-covid-19-case-traced-back.

14. Kristin Huang, “Wuhan Doctor Says Officials Muzzled Her for Sharing Coronavirus Report,” South China Morning Post, March 11, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3074622/coronavirus-wuhan-doctor-says-officials-muzzled-her-sharing.

15. Emily Rauhala and Gerry Shih, “Early Missteps and State Secrecy in China Probably Allowed the Coronavirus to Spread Farther and Faster,” The Washington Post (WP Company, February 1, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/02/01/early-missteps-state-secrecy-china-likely-allowed-coronavirus-spread-farther-faster/.

16. Kristin Huang, “Wuhan Doctor Says Officials Muzzled Her for Sharing Coronavirus Report,” South China Morning Post, March 11, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3074622/coronavirus-wuhan-doctor-says-officials-muzzled-her-sharing.

17. 荣剑 , “吹哨子的人,今天至少出来一百个版了,下面转发电影版,中国人民有智慧。 Pic.twitter.com/VgCt95sxdK,” Twitter (Twitter, March 11, 2020), https://twitter.com/rongjian1957/status/1237743031316447238?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.buzzfeednews.com%2Farticle%2Fryanhatesthis%2Fcoronavirus-covid-chinese-wechat-censored-post-emojis.

18. Josephine Ma, “China’s First Confirmed Covid-19 Case Traced Back to November 17,” South China Morning Post, March 13, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3074991/coronavirus-chinas-first-confirmed-covid-19-case-traced-back.

19. Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team, “The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) – China, 2020,” China CDC Weekly (China CDC Weekly, February 1, 2020), http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51.

20. “高福的功过祸福:虽万千人吾往矣!,” 口腔溃疡如何根治_发病原因,快速治疗方法,吃什么药,水果_口腔溃疡网, February 18, 2020, http://www.kqm8.com/renwu/1914.html.

21. Katherine A Mason, The Correct Secret, vol. 75 (Nijmegen: Stichting Focaal, 2016), 46.

22. Ibid.

23. “武汉市卫健委关于当前我市肺炎疫情的情况通报,” 武汉市卫生健康委员会 (Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, December 31, 2020), http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989.

24. Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team, “The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) – China, 2020,” China CDC Weekly (China CDC Weekly, February 1, 2020), http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51.

25.Katherine A Mason, The Correct Secret, vol. 75 (Nijmegen: Stichting Focaal, 2016), 48.

26. Al Jazeera, “Timeline: How the New Coronavirus Spread,” China News | Al Jazeera (Al Jazeera, March 19, 2020), https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/01/timeline-china-coronavirus-spread-200126061554884.html.

27. Sarah Zheng, “Wuhan Mayor under Pressure to Resign over Response to Virus Outbreak,” South China Morning Post, February 17, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3047230/wuhan-mayor-under-pressure-resign-over-response-coronavirus.

28. Josh Chin, “Wuhan Mayor Says Beijing Rules Partially Responsible for Lack of Transparency,” The Wall Street Journal (Dow Jones & Company, January 28, 2020), https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-premier-tours-virus-epicenter-as-anger-bubbles-at-crisis-response-11580109098.

29. Zhou, Xueguang et al. (2012), “The Limit of Bureaucratic Power in Organizations: The Case of the Chinese Bureaucracy”, Courpasson, D., Golsorkhi, D. and Sallaz, J. (Ed.) Rethinking Power in Organizations, Institutions, and Markets (Research in the Sociology of Organizations, Vol. 34), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 81-111

30. Katherine A Mason, The Correct Secret, vol. 75 (Nijmegen: Stichting Focaal, 2016), 48.

31. Ibid.

32. “疫情上报‘第一人‘张继先被给予记大功奖励,” 新京报网, February 6, 2020, http://www.bjnews.com.cn/feature/2020/02/06/685481.html.

33. Katherine A Mason, The Correct Secret, vol. 75 (Nijmegen: Stichting Focaal, 2016), 52.